“The Green Wind held out his hand, snug in a green glove, and September took both his hands and a very deep breath. One of her shoes came loose as she hoisted herself over the [window]sill, and this will be important later, so let us take a moment to bid farewell to her prim little mary jane with its brass buckle as it clatters onto the parquet floor. Good-bye, shoe! September will miss you soon.” (2)

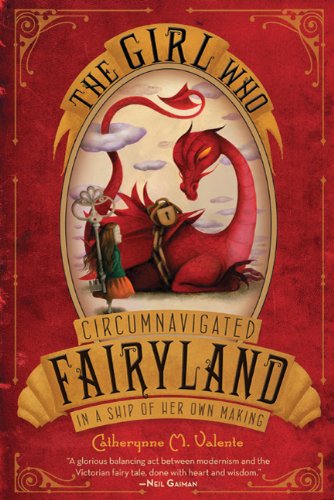

Generating a new fairy tale in a storyverse already circulating with variation upon variation of myth and fable is not an easy task to do, as seen in the case of The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making by Catherynne M. Valente. Since Fairyland’s 2011 print debut, reviewers have likened the book to works from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland to The Chronicles of Narnia to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. These comparisons seem to encapsulate efforts at categorizing The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland within the tradition of fantasy-adventure-bildungsroman narratives — finding Fairyland’s place in the ancient genealogy of fairy tales, if you will.

Valente certainly pays tribute to her predecessors (as well as to older stories that have no traceable author), but she approaches well-known tropes with a certain freshness of perspective — sometimes serious, sometimes tongue-in-cheek. From the very beginning of The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making (a mouthful of a title — one that seems to form part of a sentence, starting with “Once upon a time”), she appears keenly aware of the hundreds of years of storytelling tradition that have come before her. This awareness manifests itself most visibly in the voice of the narrator: a wry, omniscient “I” whose presence pervades the story and keeps us conscious throughout of the distance — and, occasionally, the uncanny resemblances — between our world and the story world created by Valente.

Valente’s narrator delights in exposing the mechanisms behind the traditional telling of fairy tales (just as the book itself unveils the royal “machinery” behind Fairyland’s nonsensical customs, chapter by chapter). Take this passage, for example: “One can never see what happens after an exeunt on a Leopard. It is against the rules of theatre. But cheating has always been the purview of fairies, and as we are about to enter their domain, we ought to act in accordance with local customs” (10). We are continually reminded, by dint of the narrator’s meta-commentary, that everything taking place is part of a story. However, this seeming transgression of storytelling rules doesn’t prevent readers from getting absorbed into the world of Fairyland; on the contrary, the narrator’s logical, authoritative voice strengthens our ability to suspend disbelief when things in the story take a turn for the strange.*

For while The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland more or less follows a standard, time-tested hero’s-journey recipe (call to adventure, crossing of thresholds, trials, climactic ordeal, and return), each step is given a subversive twist. For example, in her first trial (to retrieve a spoon of questionable dramatic value from the evil Marquess), September must journey to the capital city, Pandemonium, at the heart of Fairyland. How does she get there? Her guide, a half-wyvern, half-library named A-Through-L, explains: “I’m afraid the whole thing moves around according to the needs of narrative… if we act like the kind of folk who would find a Fairy city whilst on various adventures involving tricksters, magical shoes, and hooliganism, it will come to us” (51). These deliberate acts of subversion might disturb our imaginative hold inside the realm of the story, but the narrator’s voice continues unruffled, even pointing out conversationally at times the ways in which these seeming quirks of Fairyland resemble “how things are done in your [read: our] world” (52).

In effect, the voice of Valente’s narrator bridges the gap between these traditional fairy tale markers and the modern self-awareness exhibited by the characters in Fairyland. There are certainly times when the narrative explanations seem intrusive or unnecessary — serving more as a literary display than as a mode of revealing some insight not accessible from other characters’ points of view — but overall, the narrator’s presence is what lends Fairyland its distinct fairytale-like–but-not-quite** flavor. She not only links the story world of Fairyland with our world, but also mediates September’s developmental journey (from irascible child to strong, independent “grown-up”) in a way that can still draw readers who have long crossed the threshold to adulthood.

With The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland, Valente has managed to update an enduring story tradition with contemporary concerns and sensibilities. The book carves its own place in the storyverse as a folktale for those who read folktales, and also as an engaging story for those of us who haven’t outgrown the wonders of Fairyland.

_________________

*Or, more precisely, when things in the story reveal their true, convention-overturning colors. The signs that this would be no ordinary fairy tale were there from the beginning.

**The narrator assumes not only the role of storyteller (which could be seen as an evocation of the oral tradition of fairy tales past), but also as critic and tour guide, all at the same time. Her voice is present even when she doesn’t address the reader directly, as seen in the sardonic way she relates September’s thoughts or describes the landscape of particular places in Fairyland.