It is a hard enough job getting government officials to commit to reducing plastic waste. Add in persuading business owners concerned about their bottom line to limit their plastic use. For me, convincing these two groups to take action on plastic waste seems difficult and unpleasant. For Megan Byers at the Product Stewardship Institute (PSI), creating successful partnerships with them is the most rewarding part of her job.

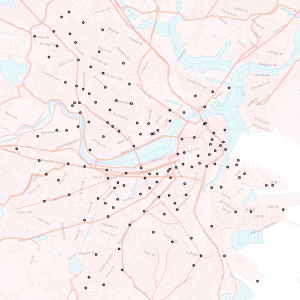

Megan Byers is an Associate for Policy, Programs, and Outreach at PSI. While PSI is headquartered in Boston, Massachusetts, the non-profit works across multiple US states to minimize the negative impacts of consumer products and packaging. Besides managing PSI’s newsletter and website, Byers promotes both legislative and voluntary plastic waste reduction strategies to commercial businesses, universities, and municipalities. At a time when the amount of plastic waste in America is at an all-time high of 34.5 million tons per year, her work with PSI is crucial.

Reducing plastic can be a hard sell. “I tried so hard not to sound like a telemarketer!” Byers said. As part of a PSI-led project in Long Island’s North Fork region in 2017, Byers had to persuade restaurant owners to implement plastic waste reduction initiatives. She did most of it over the phone. Known as the Trash Free Waters project, it aimed to get restaurants near the coast to reduce the use of disposable plastics so that plastics were kept off Long Island’s beaches. As a pilot, four participating eateries received direction and funding to switch to more sustainable alternatives. Byers notes that some restaurants were reluctant, and some were just not interested in taking part in the pilot. Her strategy? Appealing to their bottom line – making the case that reducing plastic waste would save them money.

PSI uses diverse messaging to convince restaurants and eateries to give up plastic. (Image from Product Stewardship Institute)

Byers champions PSI’s distinctive approach to environmental action: consultative, consensus-seeking, and informed by current research. The aim is to find workable solutions for the diverse stakeholders involved in reducing plastic waste. As advocating for plastic reduction always meets with resistance, her job entails being adaptable and presenting a suite of options. For example, Byers mentions that in stakeholder meetings with local government and municipal waste officials, legislative bans against single-use plastics were not a particularly appealing prospect. What was supported was public education and voluntary plastic reduction schemes.

Flexibility extends to how she conveys the reasons why reducing plastic waste should matter. “You have to diversify your message,” Byers said. “There’s a lot of other ways to frame it: it is also a social justice issue and a health issue.” She notes that PSI has a large spectrum of members and partners that includes corporate retailers, government officials, and non-governmental groups. This means that PSI’s recommendations need to be varied as well, while still aiming to minimize the negative impacts of consumer products and packaging.

Having the buy-in of all these groups is unique, especially in a time where environmental advocates often seem pitted against groups unwilling to go green. It is clear from our conversation that Byers succeeds by bringing stakeholders together. She highlights community engagement and relationship building as central to the work that she does with PSI, which often comes with pleasant surprises.

One of those surprises was how students got involved in the Trash Free Waters project: as participating businesses were set to meet with PSI in a local elementary school, two teachers came forward and volunteered their students to be involved in the project. Students participated in a logo competition. The winning logo was displayed in the windows of participating businesses.

Winning Logo for the Trash Free Waters project. (Image from Product Stewardship Institute)

“It’s really incredible how many chance meetings can turn into something bigger,” Byers reflected. The fact that students participated also attracted local media attention, which helped her promote her cause – as Byers commented, who doesn’t love a story about 5th graders trying to do good?

Community engagement does not take away from her approach of being well-informed. Creating best practices for plastic reduction is something Byers takes seriously. Part of her work also entails keeping abreast of the latest policy innovations around regulating single-use plastics and disposable foodware. She is familiar with global initiatives, such as Starbucks in the UK charging consumers for disposable cups, and India exploring extended producer responsibility schemes for plastics. The challenge is to figure out what works best and why.

“Every town is working on it separately from everyone else!” Byers explains. “My job is to synthesize all of their efforts and come up with best practices.”

Back in 2016, Byers researched trends in municipal plastic bag reduction policies. Some of this has already made its way to PSI’s website in the form of sample policies about placing a fee on carryout bags. She has also researched other forms of legislation to reduce plastic waste at its source, including requiring all foodware to be recyclable.

To my surprise, Byers shares a key insight that single-use plastic bans do not work well. Looking at plastic bags specifically, Byers notes that bans are usually written with a certain type of plastic bag in mind: bags of a certain thickness for example. The unintended result? People just switched to bags of a different thickness, which might even be worse for the environment. She remarks that bans constitute an older generation of policies; what has seemed to work better in the current landscape is to levy a fee on single-use plastics. That approach does not just ban a particular type of plastic – it can change consumer behavior.

What is next for Byers? She is excited about a future project that PSI will be carrying out in upstate New York, where they are looking to replicate the success of the Trash Free Waters project with restaurants in the city of Buffalo. Changing consumer behavior around reducing plastic use requires an understanding of what concerns various groups the most, and Byers’ consultative approach to advocacy is the way forward.