Mow, water, spray, repeat.

Mow, water, spray, repeat.

Americans spend up to six hours per week maintaining their lawn: trimming grass, obsessively spraying God-knows-what to keep the grass a bright green, turning on sprinklers at the crack of dawn— But why? What is it about these small patches of grass that fascinates Americans?

An eco-anthropological dissertation completed at Salve Regina University analyzes this very question, incorporating historical, critical, and socio-cultural perspectives. The study, which focused on one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in Rhode Island, found that American front lawns are sites of both “socially vapid” and “ecological hazardousness” occurrencess.

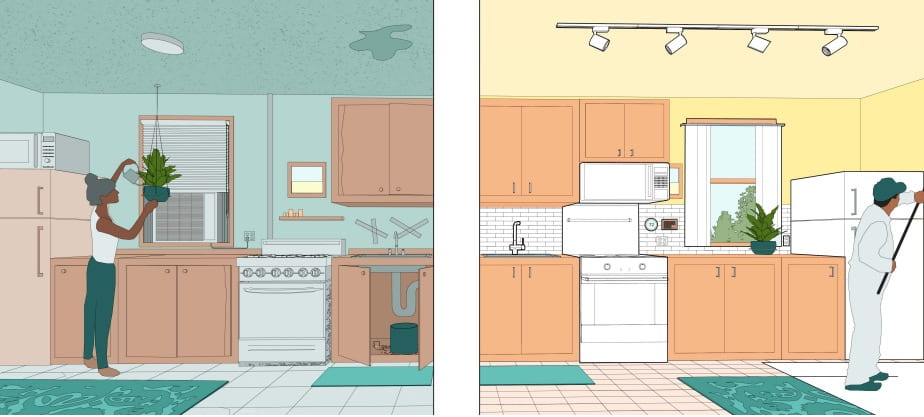

To make sense of this, let me introduce you to two houses you would probably recognize. The first house (House A) has a front lawn with long, lumpy, untended brown-ish grass. The other house’s lawn (House B) is the opposite: it is a perfectly manicured, eternally green,weed-free carpet.

Let’s begin with the dissertation’s first argument: lawns as sites of socially vapid events. That is to say that lawns are spaces where boring, unproductive, and unimportant social interactions happen.

The analysis collected data from 23 front lawns within the town of Barrington, Rhode Island. Among other questions, the study asked participants the following: Do you believe the appearance of your front lawn is a reflection of you? 68% of participants believed it was.

In American suburbs, lawns exist as extensions of the owner, measures of their character, and furthermore, extensions of American values.

The 30 billion dollar lawn industry in the U.S. thrives on the role lawns play in forming reputations with one’s neighbors, independent of any human interaction— this illustrates lawns as sites of “socially vapid” occurrences.

This makes sense to me. Families on my street always treated the residents in House B noticeably better than House A. House B treated their lawn as a prized possession and in turn, they too were treated as such. House A, on the other hand, was often the gossip on the street. People would say, “I can’t believe they let their lawn look like that” or “It’s not that hard to mow your lawn” or “Their lawn makes us all look bad.”

The goal of the dissertation is to investigate potential for a culturally viable and ecologically beneficial front lawn. Written through an exploration of people’s perception of and relationship with front lawns, the dissertation introduces larger themes important to the American lawn: individualism, control, nationalism, wealth, value, and controlled versions of nature. Understanding these themes are critical in reimagining what our front lawns can look like and how we can interact with them.

From this perspective, we can see what House A and House B’s lawns share. Neither lawns are sites of play, recreation, community gathering, or lounging. They are, as the study describes, “socially vapid.” This goes hand in hand with the second argument: lawns as sites of ecologically hazardous events.

Unsurprisingly, 80% of the study’s participants reported using a gas lawn mower, a machine already ecologically harmful in its own right. Of the 80%, 62% of participants reported using riding gas lawn mowers, the most polluting of lawn mowers.

Given the fact that our current system of lawn management and lawn use is ecologically hazardous and socially vapid, reimagining our connection to and affinity for the suburban front lawns is necessary to enact sustainable, effective change.

So, it turns out that House A is in fact less ecologically hazardous than House B. While House A leaves their lawn alone, House B’s lawn is mowed using a riding gas lawn mower.

This study shows us that the solutions to fixing our lawns can’t be found in a “top five” list. Instead, the study emphasizes that fixing our lawns is really about reimagining much deeper structures rooted in the very fabric of American culture.