When Nicole Freedman was a junior in high school, her father offered to share his 1972 Chevy Nova. “I was kind of a nerd, but even as a nerd I knew that was social suicide, so I biked to school,” she recalls with a hearty laugh.

Nearly three decades later, Freedman is a Stanford alumna, an Olympic athlete, and has spearheaded biking programs for two major U.S. cities. Recently, she made the move to Newton in order to move the town forward on transportation.

Freedman, always the adventurer, grew up in Wellesley, Massachusetts, but traveled around Europe as a child with her father, a professor at Boston University, and mother, an avid lover of architecture. It was on these family vacations that her love for cities began to take shape.

During her senior year at Stanford, Freedman joined the cycling team despite starting out as a runner. “It was a sport that I loved and a sport that I was good at,” Freedman says with a shrug during an interview in her office. Good is an understatement — she represented the United States in the 119.7 kilometer women’s road race at the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney, Australia.

In 2007, Freedman retired from a successful career in racing. Then, armed with an undergraduate degree in urban planning she had earned over a decade earlier, Freedman became the director of the Boston Bikes program. Most people simply referred to her as Boston’s “bike czar.” Speaking of the transition from non-stop training to nine to five desk duty, Freedman says, “I was truly ready. I had found something that was just a perfect match, in so many ways.”

Freedman still commutes seven miles to and from work each day. Here she is pictured with one of the ten or so bikes she owns — she’s not sure of the exact count.

Freedman entered the transportation-planning world at an exciting time. “Right before me, biking was sort of known as the 40-year-old white male in spandex that shouldn’t be,” Freedman jokes, pulling her legs up onto her chair and fiddling with some paperclips on her desk. Since then, biking has become more mainstream, potentially because of its appeal to the “hipster” faction, in which biking is seen as a cool, retro way of getting around. Having more demand and public support for bicycle facilities makes it easier for bike czars like Freedman to justify spending precious taxpayer dollars.

Freedman’s reign as Boston’s bike czar is considered by most to be a tremendous success. She is responsible for the completion of Boston’s first 92 miles of bike lanes, which is nearly halfway to the 2020 goal established in Boston’s Bike Network Plan. Other important goals of the plan include halving the number of accidents while increasing biking’s share of total traffic from around 2% to 10%; for comparison, Portland, a haven for cyclists, has a rate that has been stagnant at 6%.

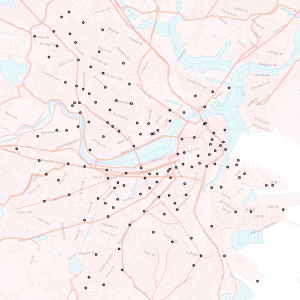

Boston’s bikeshare program, Hubway, established under Freedman’s leadership and among the first and most successful of its kind in the nation, has played an integral part in achieving these goals. The program started out small in 2011 with just 60 stations totaling 600 bicycles; by 2016, it doubled the number of stations and bicycles. The effect in five short years has been immediate: Boston was ranked the fifth most bicycle-friendly U.S. city in 2015.

A map of the Hubway network as of 2014. /Wikipedia

Whether Freedman’s tenure as Newton’s Director of Transportation is as successful has yet to be seen. City-dwellers tend to be more educated about and more open to innovations and advances in transportation, while suburbanites are very attached to their personal vehicles. Mindset and politics, as well as lack of funding, are some of the biggest obstacles that Freedman has had to overcome in all of the places that she has worked.

Working in a town like Newton, with less than 100,000 residents, can be challenging for another reason. “There’s now a formula and a blueprint for what you do in a big city, but not nearly as much for smaller cities.” Freedman adds, however, “I kind of prefer this size because you can actually get more done — from a personal standpoint, you have less levels of bureaucracy, so it’s more straightforward.”

Newton is also not your typical suburban town. There is vocal and broad support for change, due to unsafe road conditions for cyclists, pedestrians, and drivers alike. Freedman was brought on in September 2016 to help develop and implement the new transportation strategy, known as “Newton-in-Motion.” “It’s an opportunity to see the big picture and work on the big picture,” Freedman says of her newfound role.

The big picture is that American cities big and small simply cannot accommodate any more cars. Cities like Boston, Seattle, New York, and Portland, among many others, have begun to recognize this fact and take action, becoming centers of innovation and proving to each other and the nation at large that there is in fact a better way forward. “It’s very car-centric at the state and federal level,” Freedman clarifies. “So you know, it’s bottoms-up, cities, instead of states, that are the movement.”

This movement is also driven by a larger change in the transportation landscape — cars are disappearing from America almost as quickly as they arrived a century ago. The number of vehicle miles travelled per year has been declining since 2004, and unlike previous declines, this time high gas prices aren’t the culprit: Millennials are leading the charge. With this kind of tailwind, there’s nowhere for Freedman to go but forward.