When Caleb Stratton started working as the principal planner for Hoboken, New Jersey, he knew that the low-lying city was vulnerable to storm surge and flooding. What he did not know however, was just how imminent the risk was.

On October 29, four months after he began work, Superstorm Sandy pummeled New Jersey, bringing record-breaking storm surge and filling up the streets of Hoboken like a bathtub. Cutting off electricity for about 50,000 residents at its height, the storm also inundated over 1,700 homes and disrupted travel and transit around the city for months. Total damage was estimated above $100 million to private property, $100s of millions to the transit system and about $10 million to public facilities such as community centers, fire stations and schools.

But no impact was greater than that on the hearts and minds of Hoboken residents. Largely aware of the potential for severe flooding in the city, many citizens still never imagined how climate change would dramatically worsen and exacerbate their situation. Once Sandy hit, residents began to recognize the threat of sea level rise on their community and the storm helped instill a greater sense of urgency for action–even among newer residents like Stratton.

“A lot of conversations shifted from sustainability to resiliency,” Stratton explained. “The storm was a catalyst for action.”

For city planners like Stratton, Hoboken is “perfect mix” of a small-scale urban community. A dwarf compared to its cross-river neighbor, Hoboken’s strategic location across the Hudson River provides the best views of lower Manhattan, charming onlookers from its waterside walkways. The city’s coastal proximity, however, is both a blessing and a curse. Surrounded on the south, north and east by the Hudson, Hoboken had been exposed to flooding from rainfall, high tides and storm surge since people began settling on the land during the late 18th century. The city continued to rapidly develop, converting existing marshland into land that underlies buildings, roads and homes.

Although city officials and residents of Hoboken have been aware of the city’s vulnerabilities for centuries, flood mitigation was normally discussed only as a chronic problem that would eventually need to be fixed. For example, a 2002 North Hudson Sewerage Authority analysis showed that Hoboken’s combined sewage and stormwater drains were ill-prepared to handle flooding. The analysis recommended that the city install four pumps that would handle overflow caused by storm tides. At the time local officials, including Mayor Dawn Zimmer, hesitated to go forward with the project, citing cost concerns. Like other politicians and officials prior to Sandy, the Mayor also wanted more specific information about whether all four of the pumps would be necessary. By the time Sandy hit, only one of the four recommended pumps was installed.

“The combined sewer system in Hoboken has led to persistent flooding issues for the last 100 years,” Stratton explained. “But it’s only in the last five years have they built flood pumps.”

As temperatures, sea levels, and extreme weather events are all on the rise due to climate change, scientists and policymakers alike have emphasized the need for coastal communities to become more resilient. This means that those areas that are the most vulnerable to climate change are equipped to effectively respond in times of crisis in the short term and are better prepared to withstand these impacts in the long term.

Since Sandy, collective efforts by the city, state of New Jersey and the U.S. federal government have opened up more funding for resilience projects. For example, the Department of Housing and Urban Development launched a national resiliency competition in June 2013. The competition, known as Rebuild by Design, encouraged cities and communities affected by Superstorm Sandy to apply for federal money with project proposals specifically for recovery and rebuilding. With the help of Stratton and other city officials, Hoboken submitted a comprehensive water management strategy to the competition and was awarded $230 million a year later to support and begin implementation of the project.

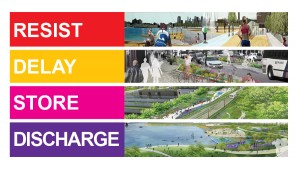

The project, which is known as Resist, Delay, Store, Discharge, is exactly the kind of project that Stratton has committed to working on since Sandy. He defines this type of planning as promoting “adaptive capacity,” which means that it allows infrastructure and people to withstand climatic changes such as rising sea levels. As such, the project is aiming to construct flood walls to protect Hoboken’s vulnerable sites from future storm surge, install a system of parks (known as green infrastructure) to soak up water and implement pumps that will help capture and eventually discharge water back out to sea.

In addition to these greater funding and collaborative opportunities, the post-Sandy recovery has also involved conversations about the disproportionate impacts of climate change on more vulnerable populations such as low-income and minority communities. These groups are often the most impacted by climate change since they often lack adequate housing, supplies and infrastructure to effectively respond and move out of harm’s way during extreme weather events.

“Without a doubt, the disproportionate impact [of climate change] to our low-income communities is a really big issue,” explained Stratton. “We are acutely aware of our vulnerable population and our most vulnerable areas. So when we develop our strategies, we look to take care of these populations first.”

One strategy that Stratton is working on to alleviate this problem is the design and development of a microgrid that he hopes will provide uninterrupted power service during future storms. As an independent electricity network, the microgrid would link together multiple energy sources from around the city to serve as a backup generator, automatically lighting up emergency buildings in the event of a blackout. In addition to providing a reliable and resilient source of energy for city buildings, the grid will also support the city’s most vulnerable residents who may not otherwise be able to evacuate in the event of another hurricane. Working closely with federal experts from the U.S. Department of Energy and Sandia National Laboratories, Stratton hopes that the microgrid will be an essential and potentially life-saving strategy if and when another Sandy strikes.

While certainly devastating, storms like Superstorm Sandy are a hard-hitting reminder that coastal cities need to be made more resilient and better prepared for extreme weather events. But has Hoboken learned this lesson? Stratton seems to think yes and no.

“We are better prepared, but are not significantly less vulnerable,” he explained, referring to the many important initiatives and projects that are already underway.

While it is true that Hoboken has come a long way in working towards a more sustainable and resilient future, Stratton cautioned that there is a considerable time lag between the planning of these projects and their actual implementation, many of which will be implemented “over years, not months”.” To this end, Hoboken is certainly taking steps in the right direction, but the mounting challenges of climate change still pose a significant risk to the city and its residents.