One of the most intense and exciting projects of the Fall 2011 semester in the Book Arts Lab was collaborating with an art history and biological studies class. This first-year seminar on the topic of the Art and Science of Food in Italy from the Renaissance to the Slow Food Movement examined herbals (essentially early encyclopedias of plants) in Special Collections. The instructors for the class, Jacki Musacchio from Art History and Kristina Jones from Biological Sciences, wanted us to create a hands-on project in the Book Arts Lab that related to these books.

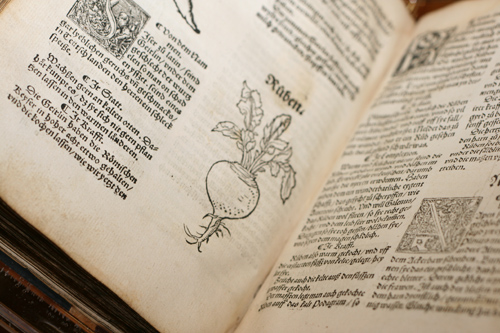

Team Book Arts — that is, Katherine Ruffin, Beatrice Denham ’14 and I — began by looking through the books that the class would study in Special Collections. Ruth Rogers, Curator of Special Collections, generously supported our research. As we browsed through the books, we were looking for a variety of things; we wanted a clear image of a plant that we could replicated by making a linoleum cut, some curious and interesting text, and paper which we might be able to simulate in the Papermaking Studio. While all of the books we examined were beautiful, one in particular stood out to us: the Kreüterbuch by Otto Brunfels.

Born in Mainz, Otto Brunfels (1488 – 1534) became a Carthusian monk, only to leave the monastery to become a Lutheran minister. He openly conflicted with Martin Luther and was dubbed the ‘first among heretics’ by the University of Leuven in 1550. In addition to books on botany, he published numerous treatises on pedagogy, entomology, Arabic, and pharmacology. He was listed by Carl Von Linne as one of the ‘Fathers of Botany,’ and the subtropical shrub Brunfelsia was named in his honor. This Kreüterbuch, literally called ‘herb book,’ was printed in 1539-1540 in Strasbourg.

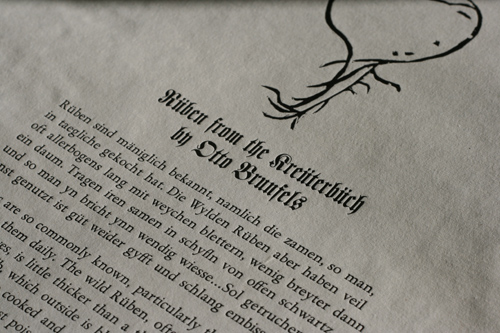

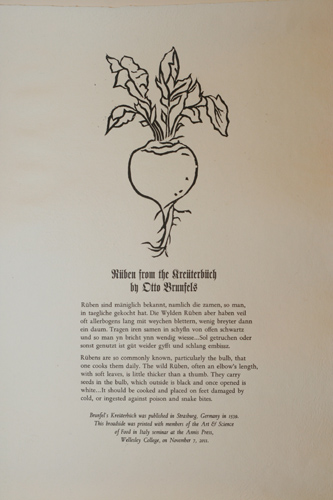

We came upon the Rüben in the Kreüterbuch, and simply could not resist the clean lines of the woodcut. However, defining what a Rüben actually is proved more difficult. (Coincidentally, all of the members of Team Book Arts speak German, and it took all of our skills to tackle this text and translation.) Through extensive research, we found that this species of Rüben is actually part turnip and part beet. Beatrice began by taking a picture of the Rüben woodcut, and then transferred it to the surface of a linoleum block with the help of carbon paper. We then took turns carefully cutting around the lines with a lino cutter so that the block would print in relief.

As for the paper, Katherine came up with a ratio of cotton, hemp and abaca that would look and feel like the paper in the Kreüterbuch. We prepared the paper by hydrating the cotton, hemp, and abaca half-stuff (that is, half-processed fiber), and then beating it in the Hollander Beater in the Papermaking Studio in the basement of Pendleton West. Meanwhile, Beatrice identified the watermark in the Kreüterbuch, a fleur de lis, and sketched it. I in turn bent five little pieces of copper wire into that form and sewed it onto a laid mould. Thus a watermark was made.

Two days later, students from the class came to the Papermaking Studio and we taught them to make paper. One of the things I love most about this job is the new vocabulary I have learned. To make a sheet of paper, you first ‘hog the vat’ (stir up the pulp in the vat), then dip in the deckle and mould, shake the paper pulp into place while making sure the fibers are evenly distributed across the mold and that there are no papermaker’s tears (indentions in the paper made by droplets of water). After draining off the excess water, you ‘couch’ the paper; that is, quickly and carefully transfer the pulp paper to a post made of pieces of felt. Once a large stack of paper and felts was built, we then pressed out the excess water with the hydraulic press, and then dried the sheets under pressure in the drying box over the weekend.

The text for the broadside proved more problematic, not least because it was written in Old German and printed in a difficult-to-read Gothic type. However, we triumphed over the difficulty posed by the text. I translated it from the Old German, and all of us took turns setting the text. Now we assembled the woodcut and the text in the bed of press SP-15, and brought over the dry paper. All was in a state an anticipatory readiness for the class, and weeks of preparation were about to come to fruition.

Twelve students and their two professors came to the Book Arts Lab on November 7, 2011, and eagerly gathered around the press. Each student printed a copy of the Rüben broadside on handmade paper using the Vandercook No. 4 press in the Book Arts Lab. As each student left with a broadside and we began to clean the press, we all agreed that this project, challenging, consuming, and demanding as it was, was also incredibly fascinating, educational, and fun.

Valentina S. Grub ‘12 is a double major in Classical Civilization and Medieval and Renaissance Studies and a student employee in the Book Arts Lab.