About the Author: Shelby Daniels-Young is a senior at Dana Hall School. These short articles are a product of her Senior Project, which was a two-and-a-half-week-long internship at the Wellesley College Archives, researching students and aspects of student life in the 1910s while learning about the job of an archivist.

Below are four articles: two reflecting on the lives of Wellesley students who graduated in the 1910s, and two describing obstacles faced by Wellesley students during that time. Research for these articles was completed in the Wellesley College Archives. The first sources used were the letters and scrapbook of Jane Cary, Class of 1914. Later sources included letters from Angeline Loveland, Class of 1916, as well as biographical files and newspapers in order to cover several topics. These articles were written with a special focus on student life and perspectives, and are supplemented on this site with photographs from the Archives.

Spotlight on Jane W. Cary, Class of 1914

Spotlight on Angeline H. Loveland, Class of 1916

A Student’s Perspective on the College Hall Fire

Money and Finance at Wellesley in the 1910s

Spotlight on Jane W. Cary, Class of 1914

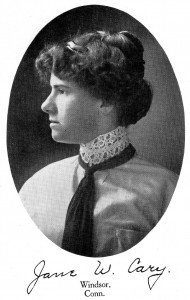

Jane Cary, Wellesley alumna of the Class of 1914, was born on July 21, 1891 in North Stonington, CT, but lived in Windsor, CT for over ninety years of her life. She was the youngest child of Reverend William B. and Harriet Cary. A member of a large family, Jane was the only girl to go to college. Though she doubted her ability to pay for such an education, she was encouraged to try by the principal of her high school.

Jane “waited on table,” washing dishes and arranging table settings, during her freshman and sophomore years in order to pay for her Wellesley education. For her junior and senior years, she lived in Fiske Cottage, a cooperative dorm, while also doing occasional odd jobs. In junior year, she joined the Deutscher Verein, or German Club. She finally graduated in 1914 with a B.A. in German. She then became a high school teacher. In 1916, at the age of 25, she married a Harold T. Nearing, and later had a son and a daughter, Cary and Jean. Jean went on to graduate from Wellesley as a member of the Class of 1944, and two of her daughters, Karen and Miriam, graduated from Wellesley in the classes of 1968 and 1978, respectively.

From 1942-1945, Jane Cary was a part of the war effort as a clerk in the Service Sales Record Office of the Pratt and Whitney Division of United Aircraft. Her shift was from 3:30 PM to midnight. She later became a clerk for the First Church in Windsor, Congregational, for 17 years. She was the chairwoman of her church flower committee and a member of the Windsor Garden Club. Jane was the only member of the Wellesley Class of 1914 to attend their 80th reunion.

The entire town of Windsor celebrated Jane’s 100th birthday. She was known as the “First Lady of Windsor” by her neighbors for her kindness and involvement in the community. Jane Cary died on June 27, 1995, at the age of 103.

Spotlight on Angeline H. Loveland, Class of 1916

Angeline Loveland, Wellesley alumna of the Class of 1916, was born on October 16, 1895 in Cincinnati, Ohio. Her parents were a Mr. and Mrs. Frank O. Loveland, with an impressive college background—her mother had an M.A. from the University of Cincinnati, and her father had a B.A. from Dartmouth College. Her younger sister, Clara, went on to graduate from Wellesley in 1921.

While at Wellesley, Angeline was a member of the Zeta Alpha society for her junior and senior years. She lived in Crofton House her freshman year, Shafer Hall her sophomore and junior years, and the newly built Tower Court her senior year. She graduated with a B.A. in English. She then taught at the College Prep School in Cincinnati from 1916 to 1920, and married a James J. Faran, Jr. in June of 1920. They had two children, John IV and Jane, in 1921 and 1922.

Angeline lived in Glendale, Ohio, for most of her life. She taught at the Glendale Public Schools from 1930 to 1947. She wrote weekly newspaper columns for the Cincinnati Enquirer from 1930 to 1961 and for the Millcreek Valley News from 1935 to the 1970s.

Zeta Alpha Society in 1916. Seniors such as Angeline Loveland and other members of her class in academic robes.

During her lifetime, Angeline committed herself to learning. She took several graduate courses in English, education, and Bible studies for pleasure. She was a member of the Monday Club in her town, a study group that required a yearly paper from each of its members, as well as the Glendale Literary Club, which required a paper every other year from members. She wrote one of her papers on the poet Katharine Lee Bates, Class of 1884, one of Angeline’s teachers at Wellesley.

Along with her weekly columns, Angeline also wrote plays for local productions, as well as songs for school and PTA performances. She helped write a history of the town of Glendale for its 100th anniversary. She held various offices in the Women’s Auxiliary of Christ Church between 1925 and 1965, and she enjoyed gardening and traveling.

Angeline Loveland died on October 11, 1983, five days short of her 88th birthday.

A Student’s Perspective on the College Hall Fire

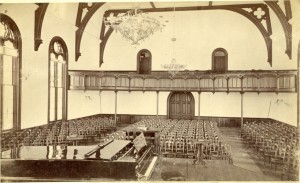

On March 16, 1914, Wellesley College senior Jane Cary sat down to write a letter to her mother. “I am writing this after coming back from a recital at College Hall,” she began. A young Bulgarian girl had performed on the violin to raise money for Bulgarian orphans. What Jane did not know was that this recital would be, as she later labeled the program in her scrapbook, “the last event in our old College Hall.”

Early Tuesday morning, on March 17, 1914, Wellesley College’s beloved College Hall caught on fire. The definite cause was unknown, but was generally suspected to be either faulty wires or a spontaneous combustion in one of the laboratories on the upper levels. College Hall was the central building on campus. It housed administrative offices, dormitories for teachers and students, a large number of science laboratories, and served as a general meeting place for students. No one died or was injured in the fire, but the college lost, among other things, valuable artwork, large numbers of a variety of records, and the personal belongings of students and faculty. In order to give the college time to recover, President Ellen Pendleton closed the school until April 7.

The newspapers wrote about lasting images from the scene of the fire. Once everyone was out of the building, students stood in a line from the burning College Hall to the library a little ways away. People rushed to save items from inside College Hall, passing the objects outside so that they could be handed down the line to safety. Mrs. Pauline Durant, the ninety-year-old widow of Henry Durant, founder of Wellesley College, requested to be brought to College Hall in her wheelchair and watched as the building burned to the ground. A sentiment that was echoed over and over again was the impressiveness of the students’ conduct. There was little hysteria, much to many people’s surprise. Many girls initially thought the evacuation was just another one of the school’s heavily implemented fire drills. Roll call was made in a calm manner, with everyone quiet and attentive, which allowed members of the college fire brigade to identify and retrieve those who were missing.

Jane Cary did not live in College Hall, but the fire affected her just as it did all members of the Wellesley College community. To her sister Helen, a few days after returning to campus in April, she wrote, “You can’t imagine how hard it is not to talk fire in mother’s letters; why it is all we talk and think about up here, everything is so different.” In her scrapbook, page after page is dedicated to the fire, filled with newspaper clippings and pictures of the ruins.

In the days and weeks after the fire, help and condolences began pouring in. Telegrams from colleges throughout the country, especially women’s colleges, asked if they could be of assistance in any way. A parent of a Wellesley College student sent a $100 check to help any needy girl in honor of the Wellesley spirit his daughter was so fond of. A widow who was not an alumna of Wellesley and who had her own financial troubles sent one dollar, with a note saying that she knew it wasn’t much, but she wanted to show “her gratitude for what certain daughters of Wellesley had meant to her.” The alumnae tried their best to help, but as one of them stated, “few are married to millionaires,” and “the majority of [Wellesley’s] single women are teachers, missionaries, [and] social workers.” It would be difficult to raise the three million dollars Wellesley so desperately needed to replace what was lost and rebuild.

Current students were not to be left out. One of Jane Cary’s classmates, Edith Ryder, sent out a notification to the Class of 1914, calling for them to contribute to the Class Fund and help the college. As seniors, the event had changed their last few months at Wellesley in many ways. Girls from College Hall were put into other dormitories, and end-of-the-year traditions had to be altered. There is another notification from Edith Ryder in Jane Cary’s scrapbook, this one suggesting that the seniors try to cut costs during Commencement week in order to be courteous to the College Hall seniors. “I propose that we dispense with Garden Party hats and with special dresses for Commencement Day and Baccalaureate Sunday,” she declares.

Jane Cary even had a little fundraiser of her own. She talked with other Wellesley students from Connecticut, her home state, and they came up with an idea. To her sister Helen, she wrote, “We are all enthusiastic about getting up a play and giving it around in Connecticut next summer…we decided to practice it up here and then give it soon after Commencement as possible.” They ended up putting on A Rose O’ Plymouth Town, in which Jane was Barbara Standish.

Money and Finance at Wellesley in the 1910s

“Thank you for the money you sent in the letter before last. It will come in handy, as it is all I have up here,” Jane Cary, Class of 1914, wrote to her mother during her sophomore year. She was a minister’s daughter, not rich by any means. She spent a year after high school working to pay for her Wellesley education. Though she managed to meet the tuition and board requirements, between school supplies, new clothes, and other expenses, her money often disappeared quickly.

What about financial aid?

According to Mary Ellen Martin 1973’s Honors Thesis, for the years 1878 to 1916, Wellesley College primarily gave help in the form of scholarships as a result of the Trustees’ morals and faith. The college predominately tried to help daughters of missionaries and ministers, like Jane Cary. They did not, however, offer aid to freshmen, which would give those with financial difficulties pause when thinking about entering the institution. Often, a student lacking the necessary finances had to take a year off to earn the money she would use to pay for her first year.

Students were not entirely on their own. There was the General Aid Committee, an organization whose purpose was to “furnish means of earning money for girls who are working their way through college.” The committee was one of the many subsets within the Christian Association. Members of the General Aid Committee helped secure secondhand books and furniture that were sold by students looking to make some money. They also notified students of odd jobs on campus and in the village. Another resource was the Students’ Aid Society, which both loaned and gave financial assistance to students who applied for it. Some of the help received was expected to be paid back at a later date.

The plight of Wellesley College students was that they were often trapped in a town that knew it had guaranteed customers. This was covered in the December 18, 1913 edition of

The Wellesley College News. A student wrote in about a faculty member’s comment regarding “the unquestioning way in which [students] accept the prices which the village storekeepers impose on [them].” Students were either desperate or did not know the proper price of the item, and stores seized on this. “[I]f we do ask the price of a jar of dried beef, for instance,” the opinion piece went on, “we do it only as matter of form, for both the grocer and we know that we will buy the beef no matter what its price.”

The college itself added to financial woes. In one of her letters, Jane Cary sadly wrote to her mother, “Don’t think I’ve been extravagant, for the precious five dollars you gave me had to go for a Botany fee.” Anyone taking a science course had to pay a fee for laboratory instruments and specimen collection. There were books to buy and class dues to pay. Every November there was a Pay Day, where all students had to pay their organization dues.

Societies, an important yet controversial part of Wellesley in the 1910s, stretched pocketbooks even more. Angeline Loveland, Class of 1916, was a member of the Zeta Alpha society. She wrote her mother in her junior year that she was “terribly worried about money. Bills amounting to nearly $6.00, society bills, tickets for Ruth + Bertha to Z.A. play…other necessaries have come in.” As the list went on, Angeline grew a little desperate. “[I]f I can possibly sell my big chair…I can make money that way,” she speculated. She had to give up going on a society trip because she didn’t have enough money. Toward the end of her senior year, she wrote to her mother again. “Be sure you send me some money,” she reminded her. “I have several bills and fees to pay, so that it is absolutely necessary.”

Many students had to write home, asking for more funds. There was more to the cost of a Wellesley College experience than tuition and board, and it was not just the treats and trinkets in the village. “I suppose you think I’m terribly mercenary + extravagant, but truly I’m not,” Angeline wrote home. She and many other students knew how their parents would feel about these repeated requests for money.

There was a silver lining to these financial difficulties, even if Wellesley students may not have realized it until years afterward. They learned how to manage their money. Angeline Loveland wrote financial accounts to her father, purposefully sending them to his work office. Jane Cary did odd jobs around the holidays so she could buy Christmas presents for family and friends. Even in a place where it was hard to keep money in one’s account, where they were mainly on their own and had to face the costly temptations of college life, these young women managed to become resourceful and responsible when it came to every dollar.

I am so impressed with these articles! An absolutely fascinating look at the past. I recommend Kit Cali’s recent thesis on financial aid students at Wellesley for more on the subject. Kudos, Shelby!