It is only fitting on the heels of Thanksgiving to have a little discussion of cooking, fire and food. Dennis Sandgathe and colleagues have a paper in Paleoanthropology reviewing the evidence for fire-control in Western European Neandertals. In the article, the authors focus on excavations at two cave localities, Pech de L’Azé IV and Roc de Marsal, both Mousterian sites in SW France preserving an archaeological sequence from roughly 90,000 to 50,000 years ago. They argue that the absence of evidence for continuous fire usage at these sites is evidence of absence of well developed fire-based technological adaptations:

Here we present evidence, based on recent excavations by the authors at two Mousterian sites in southwest France, Pech de l’Azé IV and Roc de Marsal, for the persistent scarcity of fire well after its first occurrence in the European Middle Paleolithic record. What these data strongly suggest is that while Neandertals occasionally used fire, there were also major periods of time when fires were either not present at these sites or were present only sporadically, even during periods of relatively cold conditions. As will be argued below, the near absence of fire evidence in some levels at these sites cannot be explained by taphonomic processes, excavation bias, or changes in site function, and furthermore, the length of time these sites were occupied

without using fire to any significant degree is totally inconsistent with modern hunter-gatherer use of fire

The authors of the study are excellent archaeologists, so it is hard to directly criticize their analyses of the sites they have excavated. But at the same time it is difficult to know exactly how to scale their argument up from these two localities in the Dordogne Valley to a broader understanding of Western European Neandertals. If their argument is correct, however, the most significant implication of an absence of controlled use of fire is the daily uses of fire…warmth and cooking.

Related to the issue of warmth, it only takes a quick google scholar search of “Neandertal thermoregulation” to highlight the extensive literature developed around potential Neandertal adapations associated with living in Ice Age Eurasia. In contemporary arctic populations, for example, we know populations exhibit developmental and genetic adaptations to the cold environments they occupy. And yet these populations are likely reflecting an adaptive process over a relatively small span of time (roughly, within the past 20,000 years or less) and from the starting point of advanced socio-technological systems associated with modern humans. Neandertals had a much lower technological capacity and thousands of generations more evolutionary time. Working solely off fossil evidence, we have only a limited window into potential physiological adaptations to cold.

As for cooking, PNAS has a paper in early view and associated review focusing on the nutritional significance of cooked versus raw and non-thermally processed (pounded) food.

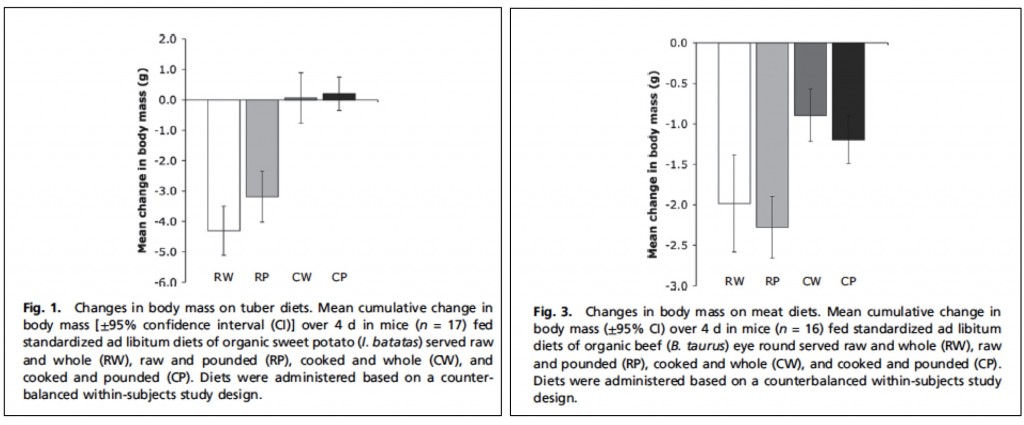

Using mice as a model, we show that cooking substantially increases the energy gained from meat, leading to elevations in body mass that are not attributable to differences in food intake or activity levels. The positive energetic effects of cooking were found to be superior to the effects of pounding in both meat and starch-rich tubers, a conclusion further supported by food preferences in fasted animals. Our results indicate significant contributions from cooking to both modern and ancestral human energy budgets.

The paper, by Rachel Carmody, Gil Weintraub and Richard Wrangham, is the latest in a long-standing research project of Wrangham’s looking at the importance of cooking and tubers in human evolutionary history. It is not, I think, surprising that cooking provides significant nutritional advantages. Cooking is wonderful. And it is nice to see a study take something other than a standard nutritional science approach to looking at the energetic consequences of cooking; in this case, using an animal model (mice) directly assessing weight loss and gain associated with different diets. I bring up the paper here because if Neandertals weren’t using fire regularly, they obviously were consuming primarily raw or non-thermally processed foods. One complaint I might make about the paper, however, is that if you examine the figures on body mass change in starch (figure 1) and meat (figure 3) diets, it becomes apparent that the vast majority of mice in the study were losing body mass. To be certain, they were losing body mass to different degrees, but an overall net body mass loss across the study population seems like an odd baseline.

As just a final comment, it is interesting the different views on fire currently floating around. There has been push in recent years to argue for the presence of fire at early Pleistocene localities in East and South Africa, while simultaneously there has been a push to argue against extensive fire use even late in the Pleistocene in Eurasia. I had long thought fire would be such a universally advantageous trait that once mastered, natural selection would strongly favor its retention, thus making the identification of that transition in the archaeological record fairly easy to spot. That is obviously not the case. I think instead what the “fire story” indicates is, in part, the very marginal demographic existence of humans until very recently, whereby even strongly positive cultural traits were subject to frequent loss due to demographic instability.

******

1. Sandgathe DM, Dibble HL, Goldberg P, McPherron SP, Turq A, Niven L, Hodgkins J, On the Role of Fire in Neandertal Adaptations in Western Europe: Evidence from Pech de l’Azé IV and Roc de Marsal, France. Paleoanthropology 2011, 216-242; doi:10.4207/PA.2011.ART54

2. Lucas, PW, Cooking clue to human dietary diversity. PNAS, Published online before print November 16, 2011, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116813108

3. Carmody RN, Weintraub GS, Wrangham RW, Energetic consequences of thermal and nonthermal

food processing. PNAS, Published online before print November 7, 2011, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112128108

I thought this paper (http://www.pnas.org/content/108/2/486) by Amanda Henry and colleauges provided pretty good evidence for some type of cooking, at least in the Belgian and Iraqi Neandertals.

Adam, I also believe that the “fire story” was marginal to certain demographics of humans existence of humans. In depth and i’m sure this post will spark a bit of holiday table debate.