UPDATE:

For some additional takes, check out Erin Wayman’s piece at Hominid Hunting (Smithsonian) and Zachary Cofran’s great discussion of these new fossils alongside the material from Malapa, South Africa, at Lawnchair Anthropology.

Meave Leakey, Fred Spoor and colleagues have a new article in Nature featuring some wonderful new fossils from Northern Kenya, dating to between 1.75 and 2.0 million years of age. This is a critical time period in human evolutionary history, as it corresponds to the early evolution of our genus, Homo. The article has gotten a lot of attention, with stories in the New York Times, two related commentaries in Nature, and I am sure numerous other stories elsewhere. I am not sure if the actual article is behind a firewall or not, but here is the abstract:

Since its discovery in 1972 (ref. 1), the cranium KNM-ER 1470 has been at the centre of the debate over the number of species of early Homo present in the early Pleistocene epoch(2) of eastern Africa. KNM-ER 1470 stands out among other specimens attributed to early Homo because of its larger size, and its flat and subnasally orthognathic face with anteriorly placed maxillary zygomatic roots(3). This singular morphology and the incomplete preservation of the fossil have led to different views as to whether KNM-ER 1470 can be accommodated within a single species of early Homo that is highly variable because of sexual, geographical and temporal factors(4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9), or whether it provides evidence of species diversity marked by differences in cranial size and facial or masticatory adaptation(3, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20). Here we report on three newly discovered fossils, aged between 1.78 and 1.95 million years (Myr) old, that clarify the anatomy and taxonomic status of KNM-ER 1470. KNM-ER 62000, a well-preserved face of a late juvenile hominin, closely resembles KNM-ER 1470 but is notably smaller. It preserves previously unknown morphology, including moderately sized, mesiodistally long postcanine teeth. The nearly complete mandible KNM-ER 60000 and mandibular fragment KNM-ER 62003 have a dental arcade that is short anteroposteriorly and flat across the front, with small incisors; these features are consistent with the arcade morphology of KNM-ER 1470 and KNM-ER 62000. The new fossils confirm the presence of two contemporary species of early Homo, in addition to Homo erectus, in the early Pleistocene of eastern Africa.

Indeed, these are wonderful new fossils, particularly the KNM-ER 62000 lower face and KNM-ER 60000 mandible. Writing for Scientific American, Kate Wong has a nice commentary on the story that includes several quotes from me, which I thought I could clarify and expand on a bit.

So, Leakey, Spoor and colleagues (as well as just about all of the other commentators I have seen) feel these new fossils provide additional evidence for multiple, concurrent species of Homo at the Pliocene-Pleistocene boundary (~1.6-2.0 million years ago). I suggest that might not be the case. What makes me so crazy? To explain, it helps to have a little historical perspective on the “problem” of early Homo.

The current arguments about early Homo can be viewed, in some ways, as dating back to the discovery of fossil material from Olduvai Gorge by Mary and Louis Leakey back in the 1960s. When the original Olduvai material was discovered it showed a combination of characters that appeared intermediate between already known South African Australopiths (A. africanus, in particular) and already known Asian (and to a less extent, African) Homo erectus such as those from China and Java. Philip Tobias, controversially, gave them the designation Homo habilis and placed them as a transitional species. Over time a lot more fossils from this 1.5-2.0 time period were discovered, and rather than clarifying the set of relationships, these new fossils simply added more and more variation to the picture. This is particularly true for the huge number of fossils uncovered by researchers in the Turkana/Omo basin region of Northern Kenya and Southern Ethiopia (e.g. KNM ER-1470, KNM WT-15000, KNM ER-3733, KNM ER-992, KNM ER-1813, KNM ER-1805 and many many more). As a result, Homo habilis, which was already rather poorly defined on the basis of features that don’t preserve well (hand morphology), are highly variable (cranial capacity, dentition size), or non-morphological (tool use), began to be viewed as representing multiple taxa. Instead of representing a transitional lineage, it came to be viewed more and more as a radiation, and the primary question of interest became how many species (Habilis?, Rudolfensis?, Ergaster?, Erectus?) and which one ultimately led to us. I had the opportunity to view most of these fossils in Nairobi in 2004 while doing my dissertation research. Indeed, while I was there, Meave Leakey and Fred Spoor were doing work on earlier published materials for Ileret, and were very kind and gracious to me in talking about their work and my own dissertation research.

One thing that made my view different was that I was not looking at the fossils from the perspective of someone who was accustomed to seeing the fossils from an African perspective. I had already been working at the site of Dmanisi for several years and had just finished a sustained period of work on the Dmanisi fossil assemblage. Dmanisi, although 2000 miles away in Georgia, is positioned smack in the middle of this critical time sequence (~1.76 Ma), but comes from a single, rapidly deposited locality, with fantastic preservation of multiple individuals and partial skeletons. And what is interesting about Dmanisi is the tremendous morphological variation present in an isolated sample. At Dmanisi we see an echo of the larger pattern of variation in the East African record, but on a smaller, more interpretable scale.

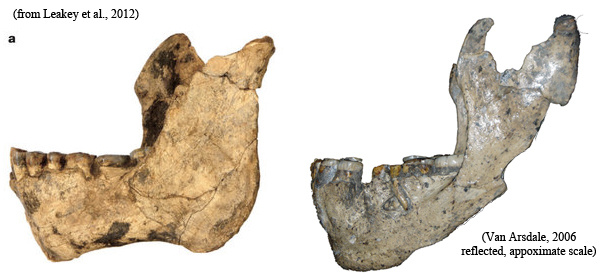

For example, consider the following image (approximate scale, the Dmanisi 2600 mandible has been horizontally reflected to allow for the comparison of its better preserved side):

Prior to the publication of KNM ER-60000, the Dmanisi 2600 mandible was truly exceptional in many respects relative to other mandibles assigned to early Homo. In particular, the size of its corpus and height of its ramus stood out. This new specimen from Kenya, dating from a similar time, is the best match we have yet for its features. And yet it is being linked to a fossil, KNM ER-62000, that has notable affinities (despite a significant difference in size) with KNM ER-1470, a fossil that prior to this publication also appeared somewhat morphologically exceptional relative to its peers. The authors also note similarities bewteen the new lower face (KNM ER-62000) and the Dmanisi 2700 individual. So in some ways, these fossils seem to be filling in a gap between earlier African material associated with habilis/rudolfensis and Dmanisi. And yet Dmanisi has already been widely associated with later African and Asian material assigned to Homo erectus, hence the description of it in various publications as basal Homo erectus.

Put simply, my initial take on these fossils is that they fill an important gap, drawing connections between two somewhat exceptional specimens (KNM ER-1470 and Dmanisi 2600) and a broader evolutionary picture of change in early Homo.

Bernard Wood, in his Nature commentary on the article, makes the argument that these fossils continue to push the range of variation in early Homo too far, evidence for taxonimc diversity at this time (he also suggests several easy to do studies that would inform this debate):

Finally, some researchers have suggested(9,10) that evidence from the face and jaws of H. habilis and H. rudolfensis, plus what little fossil evidence we have of these species’ other body regions, stretches the definition of the genus Homo too far. Perhaps these two taxa belonged to a different lineage from that from which H. sapiens arose? My prediction is that by 2064, 100 years after Leakey and colleagues’ description of H. habilis(3), researchers will view our current hypotheses about this phase of human evolution as remarkably simplistic.

This line or argument reminds me of my previous thoughts on the conflation of simplicity with taxonomic linearity in paleoanthropology. I do not think rapid evolutionary change within a lineage need necessarily be “simple.” We actually have a great model for thinking about this…ourselves. The last 100,000 years of human evolution involves fairly rapid evolutionary change. This is true for the hard-tissue elements of our anatomy that preserve as fossils, but even more so for our DNA. Yet this rapid evolutionary change was in no ways simple. It involved a massive and rapid expansion of human populations out of Africa, significant reductions in human adult mortality, a diversification and intensification of human technological production and use AND genetic exchange with at least distinct and extinct human lineages, the Neandertals and Denisovans.

A model of a single lineage of early Homo need not be simple. As a starting point, we know that there are at least two other closely related lineages of hominins walking around Africa at the time in the form of Australopithecus boisei and whatever Australopithecus sediba represents (its own species, some extension of A. africanus, or something else entirely). Thus, the presence of taxonomic diversity is already one element present to contribute potential evolutionary complexity.

An even bigger factor is simply what is going on with the evolutionary transformation in early Homo. Between 2.0 and 1.5 million years there is a significant change, even within specimens that consensus assigns to a single taxon (i.e. Homo erectus) in the form of changing proportionality in the post-cranial skeleton, cranial expansion, reduction in post-canine dental size and related changes in the face and cranial base. One might conceptualize this as a fairly rapid change from something that is ecologically distinct from living humans and apes, whatever the progenitor of Homo is, to something that has all the trappings of a nascent ecological human (technologically-mediated, cooperative, ecological generalist).

It is clear there is an abundance of morphological diversity in the early African fossil record for Homo. The consensus going back more than 30 years is that this must be a reflection of taxonomic diversity. I am not convinced that we are at that point. It is quite possible that Bernard Wood is correct and we will look back in fifty years and say we had far too simple a perspective on issues of this time. However, it is not entirely clear to me that such a view necessitates the presence of multiple taxa, overlapping in range, morphology and ecology.

There is a lot more that could be said of these new fossils, comparisons with other fossils, and arguments about their evolutionary significance….all of which will hopefully take place in time. But for now I will pause and commend the whole team responsible for providing us with these great new fossils.

*****

1. Meave G. Leakey, Fred Spoor, M. Christopher Dean, Craig S. Feibel, Susan C. Antón, Christopher Kiarie & Louise N. Leakey. New fossils from Koobi Fora in northern Kenya confirm taxonomic diversity in early Homo. Nature 488, 201–204 (09 August 2012) doi:10.1038/nature11322

What if hybridization always was a driving force of human evolution?