One of the great challenges in paleoanthropological field work is understanding the sequence of events that led to the accumulation of materials at a site. How did these sediments get here? What agents led to the assemblage of fossils that are present? How much time is represented in this or that stratigraphic layer? These are fundamental questions for the interpretation of a site, but also questions that are often not fully resolvable. In order to test hypotheses for these questions, we draw upon geology, taphonomy, archaeology, ecology, osteology, and often other disciplines. Naturally, I love these kinds of questions. Understanding a profile, such as the one above (from one of the satellite excavation areas at Dmanisi, Georgia), therefore is something that often takes years of work, but can be extraordinarily rewarding in terms of the information it provides to address important evolutionary questions.

******

In academia, an individual’s CV takes on something of the role of a stratigraphic profile. Each year, we add new layers of publications, grants (applied for and awarded), conferences, and other professional scholarly work. Having been on both ends of the job spectrum (i.e. hiring and looking to be hired), looking through the CV is an exercise in assessing “what does this candidate have?” Dmanisi has some of the most wonderfully preserved and earliest fossil representatives of Homo anywhere in the fossil record…brilliant! This candidate has an article in Nature, two in the Journal of Human Evolution, and a forthcoming PNAS piece…excellent!

An individual’s academic stratigraphy is what we have left behind for public consumption. It is the end product of our work as a scholar and researcher. And yet, it is not all that occupies our time.

******

A governing principle in evolutionary studies is uniformitarianism. The concept–often most associated with the early English geologist Charles Lyell, and recognized by many biographers of Darwin as highly influential in his own development of the theory of evolution by natural selection–refers to the tendency of change on the planet to be the result of consistent forces acting regularly over long periods of time. The oceans are shaped by incremental movements of vast continental plates, mountains rise up millimeter by millimeter through processes of uplift, and canyons are carved by the steady action of moving water over seemingly endless stretches of time.

Uniformitarianism is a guiding principle, not a law. The world is not a constant, after all, but a dynamically changing reality. Viewed from the temporal perspective of geology, events may seem long and gradual, but that incorporates a degree of time-averaging that obscures the idiosyncrasies of specific events.

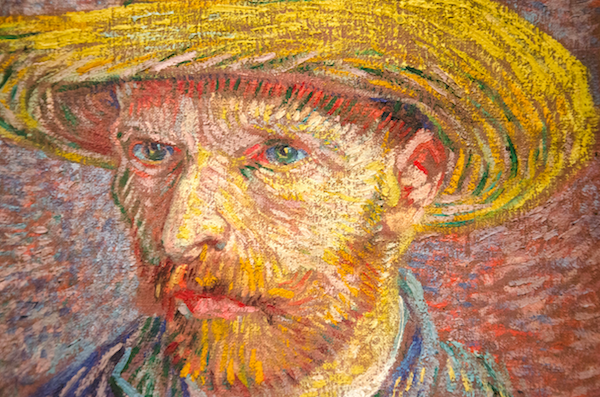

Van Gogh’s face in the self-portrait above, viewed from a few feet, reveals a red-tinged, pale face. Up close, the individual brush strokes reveal a broader palette of yellows, oranges, reds, and browns.

The Dmanisi profile above encompasses several stratigraphic time periods, ranging from the Middle Ages to the Lower Pleistocene, nearly two million years ago. The principle of uniformity, sediments and materials slowly accumulating with modification over time, holds true, even if the details of each event (and the gaps between them) are specific to each circumstance.

******

In grad school, we are trained to be diligent, academic-stratigraphic, uniformitarianists. Your goal is to produce X number of peer-reviewed publications each year, submit Y number of new grant applications each year, so that your CV can expand at a rate of Z lines per year. Put two CVs alongside one another, and maybe you can postulate how the two might look five years in the future, getting ready to come up for tenure and promotion. And as long as we view graduate school as a place to train researchers, there is not necessarily anything fundamentally wrong with that construction.

However, there is a reality that most graduate students who go on to pursue academia professionally will find themselves in jobs that have boundaries which extend beyond the CV-building training of graduate school. Teaching, advising, serving on College/University-wide committees, constructing curricula…these are all activities that are largely foreign to an incoming faculty member. They are also activities that often leave no trace, nothing durable, on a CV, despite the large amount of time they can come to occupy. A period of scholarly inactivity, in other words, may simply reflect the realities of invisible processes on the accumulation of research that is possible at any given time.

And all of this says nothing about the relentless march of life. Like an expanding universe, it merely seems to grow larger and more engrossing with each year. The simple walk from apartment to lab and back in grad school, a cycle in which life and work may be nearly indistinguishable, becomes a commute, a meeting, a class, research, and repeat. Relationships expand. Kids are born. Wonderful and tragic and trying and happy and sad moments accumulate, each of them occupying time, most of them bearing little direct relationship to what you do as a professional and what you have trained to be as an adult.

In contrasting the profiles of two individuals, it might be easy to generalize about the relative productivity of of each. It might be further possible to hypothesize reasons, different life choices and values, that might explain some of the differences. But this view can also be misleading. A lot of things are not choices, and do not present professionals with options to choose from. Sometimes we have the freedom to choose aspects of our life, and sometimes life just happens without our consent.

My own life in the past 16 months has provided me with significant helpings of each, both on the personal and professional ends of the spectrum. In my experience, this reality presents an especially challenging psychological situation. Much of our self-worth, particularly as young members of a field, comes from peer interactions: conversations at conferences about our work and progress, peer reviews, invitations to participate in scholarly activities. In other words, activities that largely reflect the durable aspects of our academic stratigraphic profile. I have never seen anyone boasting about their committee work with colleagues at the bar at a conference, even if they did boast-worthy work on said committee. Instead, conversations return again and again to the profile-accumulating aspects of publication, funding, and fieldwork. So that even at the end of an extraordinarily busy year, one might find oneself asking…what have I really done?

Ultimately the antagonistic symbiosis of life and an academic career must find some resolution, and the equilibrium point of that equation is likely a dynamic and shifting one. And that should be ok.

******

What is the point of all this? Mainly, it is a personal exercise in writing for me. When life disrupts the forward momentum of academic production, it is sometimes necessary to give it a little kick-start. This bit of writing is my own kick-start.

But I also think this is an important message, and one that young scholars do not often hear. Life happens, and that should not be an academic crime. We are trained to admire or envy the pre-graduation publications, the hyper-productive post-doc, and ultimately, the colleagues with the longest CVs. They are the peer-review certified experts. And that is fine. But I do find myself–in the midst of the busiest, though certainly not the most academically productive year of my life–more open to the diversity of my colleagues lives and work. Quantity does not equal quality, after all, and while it is nice to strive for professional practices that promote a uniformitarian ideal, that is probably not a reasonable personal goal. I am also in the midst of the transition from being an untenured “junior” faculty member, to a tenured member of Wellesley College, and therefore one who might find myself in judgement of others. That task of academic valuation, even self-evaluation, like reading a stratigraphic profile, is not a simple problem.