…for there is some one entity (or more than one) which always persists and from which all other things are generated. All are not agreed, however, as to the number and character of these principles. Thales, the founder of this school of philosophy, says the permanent entity is water…(Aristotle, Metaphysics, 983b)

Two weeks ago, while live-blogging NOVA’s new documentary, “The Dawn of Humanity,” I suggested that we need a better metaphor for evolutionary processes. This was in response to the documentary’s use of a “braided stream” metaphor to describe human evolution (more on this below), something John Hawks has been promoting for some time. Here is my attempt to provide an additional alternative.

We do need another metaphor! Not braided stream...but watershed drainage...#dawnofhumanity

— Adam Van Arsdale (@APV2600) September 17, 2015

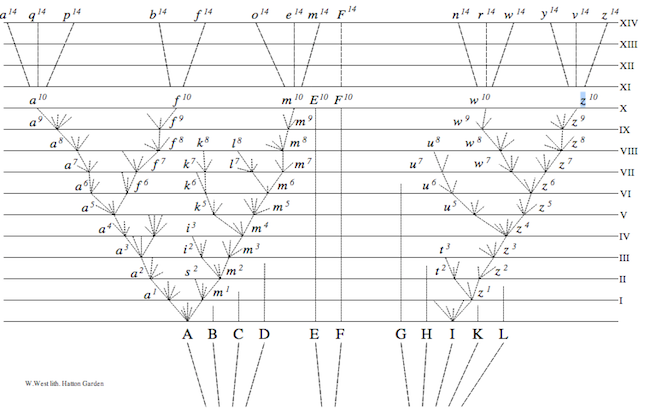

For nearly as long as the idea of evolution has been around, trees have been used to metaphorically convey what evolution is all about. Darwin’s 1859 publication of On the Origin of Species includes just a single illustration (seen below), and while it is not explicitly a tree, it’s “tree-like” nature is quite apparent.

In this sketch, Darwin conveys a number of key points about evolution. First and foremost is the notion of common descent. Living organisms (level XIV on Darwin’s figure) are descended from common ancestors in the past (found in levels I-X). Second, and perhaps equally important, is the idea that variation is an important part of a species. This is perhaps the most subtle part of the illustration, but is apparent in the short, dotted lines emanating out of the nodes in layers I-X. Evolution creates and shapes patterns of variation. It is all about variation. And finally, as evolutionary lineages move forward in time they diverge in various ways from their common ancestral states (the lateral movement of lines in Darwin’s figure). The appeal of a tree to convey all of this is quite obvious.

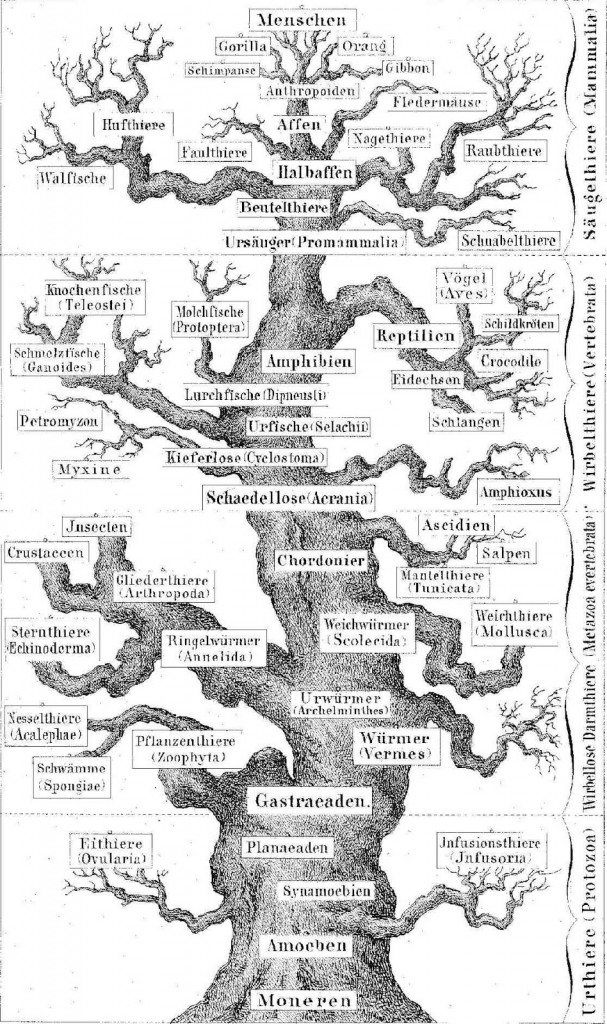

One of the first attempts to explicitly use a tree as the metaphor for evolutionary processes involving humans comes from the German biologist, Ernst Haeckel, in 1874 (see below).

While this tree still conveys the notions of common descent and the relationship among taxa fairly well, it is a less appealing figure on the whole. Haeckel reflects a dominant anthrocentrism in placing humans “Menschen” at the “top” or apex of evolution. The inherent value of greater/higher/better is hard to avoid in this representation. But my frustration with trees runs to a deeper issue.

*****

To step back just one step, it is important to recognize that implicit in Darwin’s original sketch is the biological notion that species are a real thing. Evolution sorts variation, generated by mutation, via processes of drift and natural selection, and structured by population relationships through gene flow. And it does this within species. In other words, species are real units of biology, shaped by evolution, and therefore the proper “nodes” of an evolutionary or “phylogenetic” tree. I have no problem with this. I am happy to accept Ernst Mayr’s definition of a biological species, even if we recognize today that in some organisms, particularly things like bacteria or viruses, this definition can be tricky or inaccurate.

Hawk’s preference for a “braided stream” metaphor for evolution, I think, is an attempt to recognize the difficulty in employing Mayr’s definition for evolutionary lineages evolving over time. While species may be the product of evolution’s sorting, species by themselves do not adequately describe the process by which species are generated. If we conceive of species as independently evolving gene pools, there may be times in the evolution of a lineage in which some population or populations of a species become isolated and are functionally evolving as an independent gene pool. Given enough time, this newly independent gene pool might generate enough evolutionary divergence to ensure that it remains an independent gene pool, and therefore a new species. But the generation of evolutionary isolating mechanisms, the kind that give rise to new species (particularly in things like mammals and other complex organisms), do not happen instantly. So it may be possible, looking across evolutionary time, to sample lineages that are evolving separately but have not reached the point of true evolutionary independence. Within human evolution, Neandertals are a great example of this. Neandertals persisted as a discrete and identifiable lineage for upwards of 100,000-250,000 years (with the usual caveats…to varying degrees across time and space), at the end of which, they were different, but not different enough to prevent them from contributing in meaningful ways to the gene pool of living humans.

So in the image above, a braided stream metaphor quite effectively displays what a species (or evolutionary lineage) might look like across its evolutionary time. Particularly a geographically dispersed species like our human ancestors. In this sense, I think the braided stream metaphor is great!

*****

My bigger complaint, though, reflects my desire to employ a metaphor that not only effectively conveys the product of evolution (i.e. species), but also the processes that shape those products. My problem with the tree for a metaphor for evolution is the nature of how trees branch. There are lots of different trees we could choose from to represent the evolutionary relatedness of living (and extinct) species, but they all involve branches that split discretely. One branch (or species) splits into two or more new branchs (or descendent species).

Trees with complex branching patterns (or root branching patterns) like mangroves or cypress can express more complex relationships, but they still tell us nothing about how species come about, only that they do. I think we can ask more of our evolutionary metaphors. I think Darwin managed to convey more out of his one illustration in 1859.

The answer, in my mind, is water. If we conceive of a biological species as an isolated gene pool, in which individual populations are connected via gene flow, we are already predisposed to recognize the utility of water as a metaphor. The movement of heritable material is what characterizes a species. That movement occurs to different degrees, in different ways, depending on the ecology of the organisms in question. In other words, some evolutionary lineages readily create new species (forming “bushy” phylogenies) and others do not (forming more “linear” phylogenies). Darwin seems to have been well aware of this in his original sketch above. How do we convey this with water?…by thinking about how water moves through drainages in varying ways depending on the substrate and topography of a landscape. Species exist on different evolutionary substrates (more or less “speciose” or prone to development of reproductive isolating mechanisms) and on different evolutionary topographies (narrow and broach niches).

Some drainage systems are strongly constrained. As an evolutionary metaphor, this can represent as well as provide some explanation for why some evolutionary lineages remain relatively static or “linear” for long periods of evolutionary time.

Other drainage systems meander and separate across the landscape freely, relatively unencumbered by topographic or substrate constraints, in the same way perhaps that some evolutionary lineages rapidly differentiate.

*****

One of the main stumbling blocks for some skeptics of evolution is the process of speciation itself. These people are happy to accept that species change over time (“microevolution”), but have trouble accepting that new species have arisen via evolutionary processes over time (“macroevolution”). Talking about trees doesn’t help this confusion. While an evolutionary tree represents something about how species are related, contrary to Darwin’s 1859 illustration, it really does not tell us anything about the process that gives rise to species or the variation inherent in that process!

Water flows…in much the same way that heritable material is exchanged within and between populations in a gene pool. The movement of water throughout a drainage system can therefore represent not only the relationship between related species, but also tell us something about the evolutionary processes which have shaped the different pattern of species that we see. Watersheds have the added bonus of giving us a little more flexibility to consider processes like introgression, the periodic movement of genetic material between species (think “floods” or “rain”).

Following the recent Calpe 2015 conference via twitter, it was fascinating to (virtually) see a discussion among prominent anthropologists about the proper use of species concepts in paleoanthropology. Even professionals struggle with this! And the struggle isn’t, largely, about how to convey the relationship between species. It is about what processes are important in generating lasting evolutionary differences. In other words, it is about the topography and substrate on which human evolution is taking place. I think we can all agree that we can recognize evolutionary differences, the challenge is how we assign value within a taxonomic system to those differences. Recognizing that engaging in “species argument” in this context is not really about the name, it is about the process, a better metaphor can help.

I love trees. Trees do a pretty good job of representing how things are related. But I love water even more. As a metaphor for evolution, water has the added advantage of potentially telling us not just about the relationship between species, but also the unique processes by which species are created. Or so I think…

Hi Adam! I enjoyed this post, and generally agree that water has a lot more potential for accurately conveying the realities of genetic evolution. However, I think it must be said that trees (or perhaps a discretely-branching river) still do a better job when zooming out to consider the phylogenies of higher taxa (e.g., mammals vs birds).

Even though clean branching events are probably rare in nature, actual branches do often result given sufficient time. So when dealing with basic evolutionary relationships between, e.g., humans and other extant primates, a tree might still be best even though the hominin/Pan/Gorilla split is better represented as a braided stream if one is interested in the specifics of how it occurred, and watershed drainage might better represent the evolution of more recent Homo than even a braided stream would.

I doubt I’m saying anything new here; I just find the application of different metaphors depending on the scale of the question to be a nice prospect.

The problem – or perhaps it is a benefit – to using water is that in a watershed, rivulets coalesce into streams, that coalesce into rivers, etc. That makes water a natural metaphor for talking about gene coalescence, backwards in time. But if you want to talk about speciation and splitting, forwards in time, you have the issue that in a natural landscape, the flow of water is in the opposite direction to the arrow of time.

I’ve been thinking about this while co-writing the second edition of The Ancestor’s Tale, which does the backwards-through-time thing. But that’s not what I would call standard.

This is true. But water circulation is, more or less, a closed system, which is nice and consistent with evolutionary processes. And this would certainly not be the only “backwards” metaphor in evolutionary thinking. Wright’s adaptive landscape, with fitness “peaks,” is another backwards metaphor, giving natural selection anti-gravity properties instead of a more natural gravitational pull.

Hmm – not sure what you mean by ‘closed system’ – is there an analogy with evaporation & deposition high up a watershed? The number of copies of a genome is not obviously limited in a closed manner, and I’m not sure measures of information flow are either.

Certainly backwards metaphors are quite reasonable. That’s the whole point of the Dawkins book I am (re)writing, after all. As for river metaphors, you might like this sort of thing, by the way.