I am an anthropologist. Within that broad heading, my work falls into the sub-field of biological anthropology, meaning I use evolutionary theory to address questions about human variation, past and present. I specialize in paleoanthropology, with a particular focus on questions of evolutionary change and processes in the Pleistocene, a time period spanning the past 2.5 million years. This time period covers the first appearance, spread, and subsequent evolution of our genus, Homo, from its African origin to its current ubiquity on the planet.

My primary research interests are in understanding patterns of morphological variation in the fossil record. My dissertation was an analysis of fossil mandibular variation from the Lower Paleolithic site of Dmanisi, Georgia (see below). Since that time I have continued to address questions regarding the pattern of variation in the earliest fossils assigned to the genus Homo, in the hopes of adding to our understanding of this important evolutionary event. My morphological interests are not limited to early Homo, however, but extend into questions of bone biology and development, as well as the methods we use to generate fossil-based knowledge from contemporary, comparative analogs.

My primary research interests are in understanding patterns of morphological variation in the fossil record. My dissertation was an analysis of fossil mandibular variation from the Lower Paleolithic site of Dmanisi, Georgia (see below). Since that time I have continued to address questions regarding the pattern of variation in the earliest fossils assigned to the genus Homo, in the hopes of adding to our understanding of this important evolutionary event. My morphological interests are not limited to early Homo, however, but extend into questions of bone biology and development, as well as the methods we use to generate fossil-based knowledge from contemporary, comparative analogs.

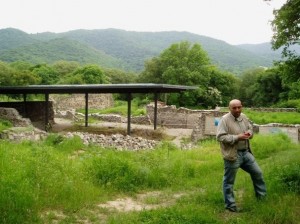

A significant part of my research involves paleoanthropological fieldwork. I have been associated with the excavations at the site of Dmanisi since I began graduate school, including helping to initiate and coordinate the Dmanisi Field School at the site. This site is the earliest well-documented fossil hominin site outside of Africa, dating to more than 1.8 million years of age. The site has provided one of the most abundant and well-preserved fossil Homo assemblages in the world. Dmanisi is a uniquely positioned fossil locality for the integration of understanding fossil hominin variation with behavioral and environmental data derived from collaborations with paleontological, archaeological, and geological specialists.

A significant part of my research involves paleoanthropological fieldwork. I have been associated with the excavations at the site of Dmanisi since I began graduate school, including helping to initiate and coordinate the Dmanisi Field School at the site. This site is the earliest well-documented fossil hominin site outside of Africa, dating to more than 1.8 million years of age. The site has provided one of the most abundant and well-preserved fossil Homo assemblages in the world. Dmanisi is a uniquely positioned fossil locality for the integration of understanding fossil hominin variation with behavioral and environmental data derived from collaborations with paleontological, archaeological, and geological specialists.

More recently I have begun expanding my field interests to broader, regional questions of hominin biogeography. In early summer 2013, I joined international colleagues on a preliminary set of surveys at several Pleistocene localities in Kazakhstan. Archaeological and genetic research have revealed important connections across Eurasia, and yet Central Asia is a largely unknown region for Paleoanthropological research. Our aim is to help fill in this (large) gap. I am currently involved in a National Geographic funded project doing exploratory work in South-Central Kazakhstan with the aim of identifying and documenting a hominin presence in the region, with the real hope of trying to find a well-stratified hominin site. I also have previous field experience in the Central Rift Valley of Kenya, in the Tugen Hills region.

In addition to my work with the human fossil record, I am interested in the connection between the evolutionary understanding of human variation and human society today. This extends to issues of race, health, and the propagation of personal genomic data within society. If patterns of biological variation do not fundamentally reflect racial patterns (and they do not!), why do ideas regarding race and its association with biological variation persist? How is our biology, including its homeostatic drive, a product of our evolutionary past? What does it mean for our understanding of ourselves (and of each other) to have fingertip access to the vast, but complex set of data encompassed by our genome? Each of these questions can be viewed and addressed from an evolutionary perspective, with a critical eye towards the actions of evolution in our past and how the complex human cultural environment has shaped our pattern of evolution.

I have also been involved in a number of projects aimed at improving public understanding of human evolution. In 2013 I launched an open-access, web-based course on human evolution done in partnership with EdX. That course, while not currently live, is very much available and free to the public. It includes 12 weeks of interactive content, including more than 160 video lectures, virtual labs, readings, and assignments. More recently, I have been developing a virtual-reality (VR) based platform for the exploration and learning of human evolutionary anatomy. This platform includes high-resolution scans of fossils and extant comparative human and primate skeletal material. I’m hoping that at some point soon this will be publicly available and accessible with a smartphone.

Professor VanArsdale,

I just finished your Human Evolution course (along with thousands of others). I just wanted to say how much I enjoyed the course and how much I learned from it. I have to admit I only took the course because it was from Wellesley (I’m Wellesley 1966!), and I wasn’t overly interested in human evolution. I really wanted to find out if I could still pass a course at Wellesley!! Well, I did. But along the way, I learned how fascinating the field is and how good the Wellesley professors are today. I plan to follow your blog with great interest. Thank you so much for teaching the course–and teaching it so well!