The Pseudo-Science of Race

in the Enlightenment

by Molly Hoyer, Shivani Dayal, and Rachele Byrd

When studying the Enlightenment, the self-professed Age of Reason presents a challenge: because intellectual thought during this time period was based entirely around reason and objectivity, the era is associated with significant scientific and academic progress. Kant’s major works are critical to any philosophy curriculum, Von Linné is considered the father of modern taxonomy, and Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, is widely recognized as one of the first naturalists to address the phenomenon that we now know as evolution. But despite the immense scientific progress made during the Enlightenment, key stepping stones like genetics, evolution, and anthropology still had a long way to go. A lack of information is typical within the process of scientific progress, but that void becomes problematic when significant portions of these bodies of work are devoted to classifying and analyzing humans based on incomplete information and when that incomplete information is then used to perpetuate preexisting racial ideologies. This problem is accentuated by the fact that these classifications and analyses heavily influenced later scientific and sociological thinking but were rarely questioned due to the touted “magnificence” of the Enlightenment era.

The observations Enlightenment thinkers made frequently came to problematic conclusions. Georges-Louis Leclerc noted that there was a gradient of skin colors down the earth’s latitude and that there was also a gradient of climate down that same latitude. From these observations he concluded that “climate is the principle cause of the varieties of mankind” (22). He expands upon this idea by stating that people, “after spreading all over the whole surface of the earth, have undergone various changes by the influence of climate, food, mode of living, epidemic disease and the mixture of dissimilar individuals” (27). The process that Leclerc is essentially describing is natural selection. While this understanding is not false, Leclerc must be held accountable for the way he uses his observations to perpetuate a hierarchy of racial groups. He makes statements referencing how people who do not live in cities are “savages” and “uncivilized” and therefore “ugly” (26). His language helps illustrates the way that Enlightenment thinkers often leapt to dramatic and unfounded statements regarding what skin color indicated about a certain group’s character and disposition without providing substantial scientific evidence to back them up. In another example, Leclerc notes that black babies are often born lighter-skinned with blackness centered around their navels and genitals which would then spread across the body over the course of a few days (24). He used this observation to justify his claim that black people were inherently more sexual–another instance of science being used to “explain” a perceived racial difference when it was really preexisting racial ideologies that were filling in the gaps of scientific knowledge.

Despite not having a complete understanding of genetics, Enlightenment thinkers realized that skin color was an inheritable trait, and went so far as to characterize and classify skin tones that arose due to specific cross-matching of people. For example, Kant states that if a “mulatto” marries a white, then their offspring are a “terzeron.” As long as each new generation marries a white person, the term used to label the child indicates a growing distance from any blackness, but once a child marries a mulatto, their child is said to go “backwards” along the color chain (61). Such language clearly demonstrates character judgements attached to skin color and its inheritance, without a complete understanding of how that inheritance works. It was another way scientific observations were manipulated to reinforce social norms and make moral judgments.

The dramatic claims about character traits and inherent natures were pushed even farther by philosophers and writers of the time. As the editor of Race and the Enlightenment, Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze, says, “There is, so to speak, quite a promiscuous theoretical as well as stylistic dependence of one writer on another” (6). Writers during the Enlightenment would often cite one another and in this way continuously build up support for their arguments. This practice led to a reliance on cultural and social norms to fill in the gaps of information that science could not yet provide. For example, Kant writes extensively about national stereotypes, or characteristics, but provides little to no scientific information until he references Hume when discussing Africans. His descriptions of Europe are accurate because he has an extensive knowledge of their societies and cultures, but once his analysis leaves Europe, he is completely reliant on outside sources who often did not have a complete understanding of their own field.

While these Enlightenment thinkers contributed significantly to philosophy and science, their role in using pseudo-science to establish and perpetuate racial differences and stereotypes must be acknowledged. The process of attempting to define racial difference with incomplete science did not end after the Enlightenment. In all kinds of scientific communities, people are still searching for a biological explanation for racial differences. For instance, despite the fact that genetic studies have shown that 99.9% of all humans have the same DNA, current health studies still group participants into racial categories in order to address how a disease might manifest differently in different races. While it is true that diseases may take shape differently in different people, this type of grouping subtly reinforces the idea that there is actually a significant biological difference between racial groups when in reality most of these health studies are actually attempting to control for the social determinants of health (i.e., socio-economic status, etc.). Today, just as during the Enlightenment, the subtleties and nuances of race are often sacrificed in the name of science.

***

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, “The Geographical and Cultural Distribution of Mankind,” from A Natural History, General and Particular, in Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze, Race and the Enlightenment: A Reader. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1997.

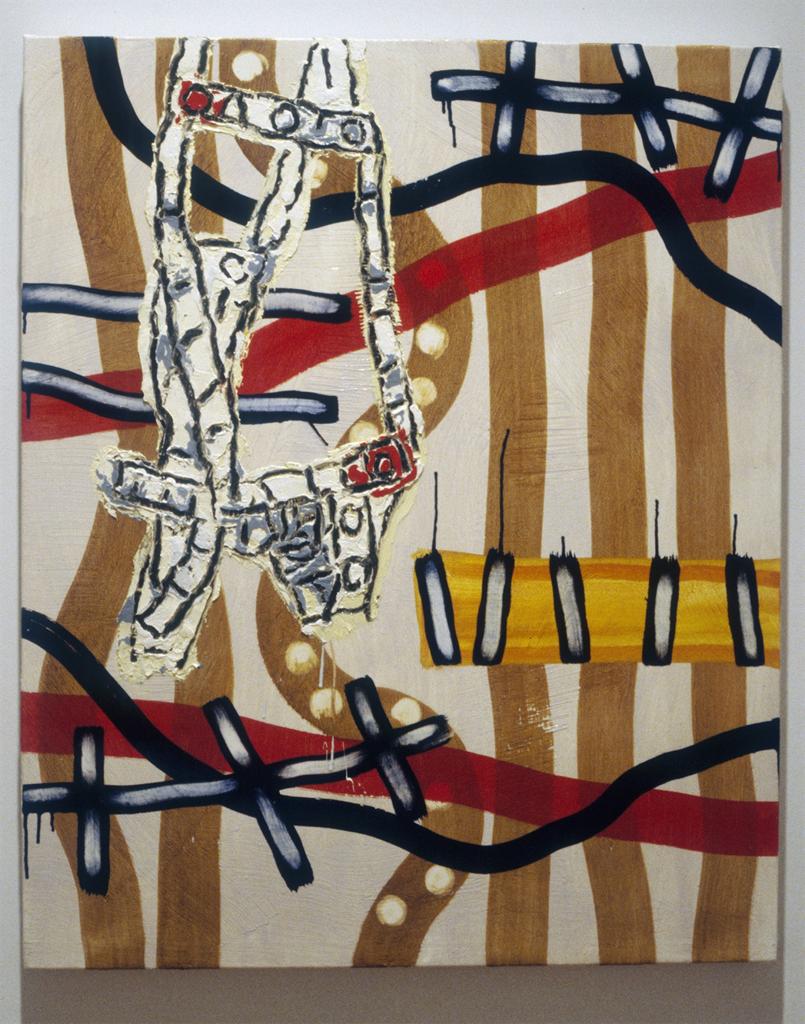

Photo: David Urban, “Latin Genetics,” Courtesy Larry Qualls via ARTstor.