by the Census Critics

The categories and language used on the census have changed with every iteration—to reflect the new administration’s social usage of racial and ethnic terms. Since race is a social construct, the terms used regarding race and ethnicity are often confusing, biased, and defined differently by different people. The Census Bureau hopes to mitigate the discrepancies in the language on the census by removing the term “race” and replacing it with the phrase “Which categories describe Person…” (Pew) in 2020. This could be a big step in changing the perceptions of the power of race because weight could shift to the ethnicity category. The white category would be broken into smaller groups.

This would not be the first time the Census changed the way it recorded race. Before 1960, official census-takers chose the racial category for each American they counted; they followed a set of strict rules in order to control who could be identified as white based on how much “blood” of other races they had. The word “race” was briefly removed in 1980 and replaced with the phrase “Is this person…” and followed by a list of categories. While the label “race” was reinstated in the 1990 census, the 1980 census was the first to allow Americans to identify themselves without using the word. It allowed Americans of color in particular to describe themselves on their own terms. The Census’ decision to allow Americans to identify themselves, and temporarily end the practice of compelling Americans to use the word “race” to describe their identity, were two important steps away from the idea that race is inherent and indisputable.

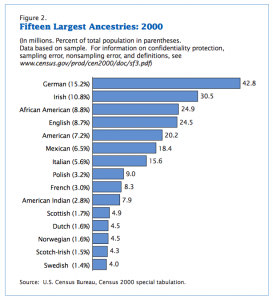

Race is a social construct based on power. With the erasure of race from the Census, a new power dynamic will be offered to Americans filling out the form. This theory is best exemplified through an existing chart (pictured below) from the U.S. Census which displays the fifteen largest ancestries or ethnicities (remember that the U.S. uses these terms mostly interchangeably). This chart is from 2000 and the analysis is based on the data from that year, with the assumption that these trends will remain largely intact. The two largest ancestries, German and Irish, belong to what we would call the “white” race. The next largest ancestry is that of African-Americans, a group still unable to be properly assigned its ancestries due to the violent assimilation forced upon many of its members during and after slavery. Another signifier of how power dynamics change with the introduction of ancestry, combined with the absence of race, is the American Indian category. While the category is the smallest when comparisons are based on race, the category rises to tenth on a list of the fifteen largest ancestries. American Indians comprise a larger group than the Scottish, Dutch, Norwegian, Scotch-Irish, and Swedish categories respectively. These ethnicities, which as a race would be classified under the dominant white category, now migrate to the very bottom of the list. Whiteness is no longer a comprehensive unit, and perceptions of power are sure to change if ancestry and ethnicity become the more dominant classifiers of identity.

The U.S. Census has come a long way from a few select government employees gathering census data from the population. When it allows citizens to self-identify using an ever-changing terminology, and with the current (and very real) possibility of removing the word “race” from the census, the U.S. Census has greater value than it would if it merely sought to identify the people that make up the U.S. population. By changing the way “race” is used and described or removing it altogether, the U.S. Census may have long-term effects on perceptions of race, ancestry, and ethnicity. The census has the power to redefine how the people of the United States see themselves and one another.