by The Census Critics

The U.S. Census is the way the United States collects population data from its citizens every ten years, and it uses racial categories set by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). The census often shapes and reflects the way we talk about race, acting as a guide to what language we use. For example, both slavery and war have greatly impacted the language in the census, as “free” and “slave” were both used as markers of race in the late 1700s and early 1800s. The census does not always reflect current language. At the same time, it often impacts the language we use around race because it is a government-issued document. In the past, “Chinese” was the only racial descriptor for those of Asian descent, and since then, the Asian category has remained disproportionately representative of East Asians. This has led many to think only of East Asians when confronted with the term Asian. As the director of the OMB is a cabinet position, the next census in 2020 may be affected by the language of Donald Trump and his administration, prompting additions or retractions of language on the census to reflect his views. The Trump’s administration’s stance on immigration is highly racialized, with images of “bad hombres” from Mexico and “terrorists” from Africa and the Middle East. In the era of Trump, Arab and Persian communities have been especially othered, leaving the question: how will the Asian racial category change in the 2020 census? Will the new U.S. census attempt to define and other the Arab Asian community by introducing more specific categories, or will the administration attempt to other Americans in this community by leaving them unnamed on the census?

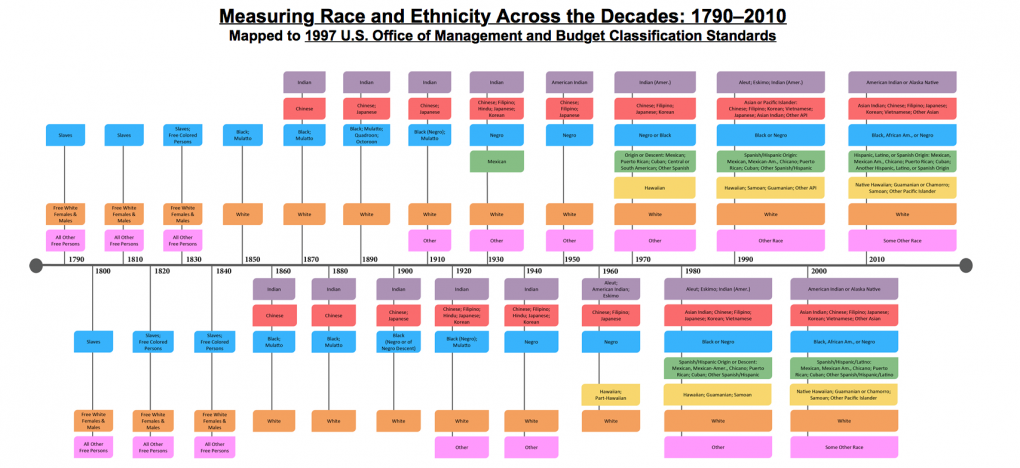

From the first U.S. Census in 1790 to the most recent U.S. Census in 2010, the racial and ethnic classifications used by the census have gone through extensive changes. As one can see from the most recent form of the census, some groups, such as those of East Asian descent, have been provided with several different names that are mostly derived from country of origin: Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, etc. Other groups, such as those of Caucasian or European descent are combined into a single category: White. However, groups such as those of Middle Eastern descent have no names provided by the census, leaving those who identify as such with no clear way to respond.

The terminology used—or omitted—by the U.S. Census can shape how people think of racial groups from around the world. The opposite is also true: preconceived, widely-held notions about race can help determine what appears on the census. For example, most American people don’t think of “Asians” beyond those of East Asian descent. But what about Afghan people, who are from South Asia? Or Iraqis, who are from Western Asia? With the most recent form of the census taken in 2010, Afghans and Iraqis would fall under “Other Asian.” But now that the United States has fought in both the Iraq War as well as in the War in Afghanistan, and with the new administration of the United States, people from those regions may be seen as different, other, and “un-American.” Because of these changes in America, Afghan and Iraqi people may find themselves with different racial categories in the 2020 census.

History has shown that the Asian category has changed with conflict. The Korean War started in June of 1950, and Korean as a race was omitted from the census that year even though it had been on the census since 1930. Something similar happened with Vietnamese as a race; it was not added to the census until the end of the Vietnam War. In both of these cases it is likely that the census did not reflect the viewpoint of most Americans, as the wars with Korea and Vietnam would come up in daily conversation. These specific instances are not cited to imply cause and effect, but rather to say that conflict does influence the census even when the addition or omission of an identity contrasts with popular language and racial commentary.

As of now, the Trump administration has not shied away from expressing conflict with other countries. So far, the list includes Mexico, China, Libya, Sudan, Somalia, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Yemen, and Palestine (which the U.S. does not recognize as a country). While the United States has had past conflicts with some of these countries prior to the Trump administration, no administration has been so full of overt vitriol that has so easily engaged the public. Despite Middle Eastern and Arab identity becoming topics du jour for American politics, these identities have not been specified in the U.S. Census. Omitting these Asian identities in the census would further other these identities, making Middle Eastern Americans and Arab Americans appear un-American; however, adding these identities to the census could provide data for surveillance on these communities, for which Trump has advocated. Whatever the reasoning, it is not likely for the Asian category in the U.S. Census to stay the same during this administration.

Image from the United States Census Bureau: Measuring Race and Ethnicity Across the Decades: 1790–2010, U.S. Office of Management and Budget Classification Standards.