by “The Fake Philosopher,” Malaysia Johnson

Racial identity has been used to a great extent in biomedicine, forensic anthropology, law enforcement, etc. It has been a common variable in studies of human difference through the ages, particularly physiognomy—the art of deciphering a person’s character from her appearance—in the classical and medieval periods, and human evolution in modernity. Kittles and Torres, two modern day geneticists, use the human genome to try and identify our evolutionary origins and determine how we are all different. In their research, they have determined that our genetic makeup is 99% the same with only slight variations that have nothing to do with race and ethnicity. They then conclude that race is a socially constructed idea, as opposed to a collection of testable subject groups that each bear evidence of a relationship between physical appearance and character, as physiognomers suggested. This could lead some to believe that premodern physiognomers were more ‘racist’ than modern scientists.

As an African-American woman who grew up in a rural town in Southern Maryland, I have experienced racism. Through the years, I have tried to keep up with and participate in our long winded national dialog about race. When faced with racism, I often wonder “why listen?,”, decide that the racist claims have no real basis, and then disregard them entirely. However, many on the receiving end of offensive, racial remarks do not ignore them. In contrast, some take those remarks to heart and become discouraged or ashamed of their racial identity. Why would anyone listen to unsupported theories that suggest some races are superior to others? Why believe there are ‘differences between the races’ beyond phenotype, especially when faced with scientific data like that of Kittles and Torres? As our society progresses in technological and scientific innovations, we have put more and more of our trust in institutions of higher education and the scholars they produce. Though religion and spirituality are still sacred to many people, as upcoming generations continue to invest in higher education we can reasonably expect more people to focus on intellectual and scientific approaches to the human condition. Yet this is no answer because science is not immune to racism.

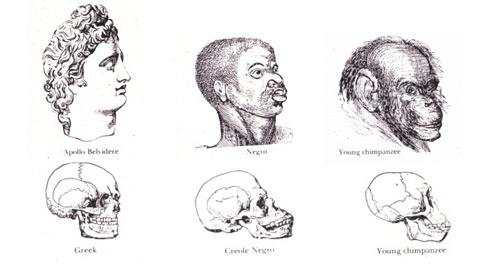

Time and time again, ‘scientific’ studies on race have proven to be biased toward the race of the examiner (often Caucasian) and lack any real scientific support at all. For example, craniometry (see figure above), the measurement of the cranium in order to test intelligence, was used to identify Africans and African-Americans as inferior to Caucasians and, thus, to justify the continued practice of slavery. Also, some evolutionary theorists skewed data to prove that those of darker complexions were a type of sub-human, closer to primates than Homo Sapiens. These and theories like them have left a stain that persists, affecting our cross-racial dialogue and relationships with one another to this day. These ghosts, though less frequently justified in educational institutions, are still discussed as if they hold true in numerous social environments. Race remains a huge factor dividing some people from others, so when Kittles and Torres suggest it is something we have made up in our heads, my head begins to swirl: Could centuries of the study of race and ethnicity be tossed out the window? More importantly, could all of the turmoil we have caused each other over race finally be deemed a colossal waste of time? As we explore the realms of classical, medieval and modern physiognomy, my question is just that: Could physiognomic study be not a credible practice but rather a calculated bias? Does physiognomy, long considered a science, show us that science has had a long and storied racist history?