When he was younger, Bruce King says he had a keen sense that he “was part of a big machine that was wrecking the planet, and wrecking other human beings and other species.” Today, King is a renowned structural engineer leading the green building movement. His ambition, which he believes the building and construction industry should aim for, is to turn buildings from carbon sources to carbon sinks.

In an interview with King, he shares his story and how he’s making the building sector more green. With a little chuckle, King begins by recounting how he ended up in Architectural Engineering school at the University of Colorado-Boulder back in the 1970s. He describes himself as the “oddball with a ponytail and tie-dyed t-shirt.” King explains he landed there because his father suggested it, King was “good at math, liked to build stuff” and well, because he “hadn’t really thought of anything else to do.”

Bruce King

Bruce King

King’s green-building career started after graduation. By chance, on a fishing and backpacking trip with mutual friends in the mountains of California, King’s home state, he met Sim Van der Ryn. Ryn, a prominent architect, author, professor at UC Berkeley, and a Guggenheim recipient, saw King’s potential. After the trip, Ryn called him and asked him to engineer a straw bale building for one of his clients. Intrigued by the project, King remembers the conversation was as simple as: “Straw bales? Yeah. Sure.”

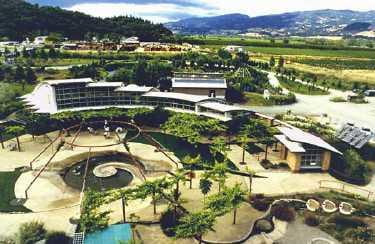

That project became the Real Goods Solar Living Center in Hopland, California. The center opened in 1996 as the Solar Living Institute’s headquarters for sustainability education and a Real Goods retail store for renewable energy systems. It is still King’s most fun and memorable project. The center was a huge success. It stayed cool in the summer and warm in the winter using only the sun’s radiation and straw-bale insulation.

This project convinced King of the potential of straw bale construction— what he now says completes the iconic “American trifecta,” next to Democracy and Jazz; all three were invented in the U.S. and have influentially spread all over the world.

The Real Goods Solar Living Center

Despite its success, natural building projects like the Real Goods Solar Living Center were rare. But as one of those hippies, natural projects like the Real Goods Center showed King how green building strategies could be widely implemented to improve the construction industry’s sustainability. In the past couple of decades and arguably in the past few years, mainstream builders have started paying attention.

According to King, annual net CO2 emissions from the building and construction industry is roughly 22 gigatons. To reduce emissions, King is advocating for what he calls a “low-carbon diet.” The diet focuses on reducing the embodied carbon emissions of buildings through the widespread use of natural materials and the implementation of green building policy. Natural materials, like straw and wood, absorb CO2 from the atmosphere via photosynthesis when they are grown. Building with those natural materials, which are made of carbon, prevents that CO2 from being later re-emitted into the atmosphere. Instead, it is locked away in the built environment.

But King believes the industry can do more than just cut emissions. He believes the industry can become a carbon sink, storing 15 gigatons of carbon in buildings annually by 2050. Dubbed “15×50,” King and Chris Magwood, a fellow author and sustainable designer, introduced the ambitious, but achievable goal in their 2022 book, Build Beyond Zero.

15×50 Goal from Build Beyond Zero

15×50 Goal from Build Beyond Zero

But why would the building sector ever voluntarily implement a low-carbon diet, cutting emissions and changing its ways to build with green materials? King says it’s simple: “They’re going to have to. The rules are changing.”

Laying out how policy drives change, King mentions the General Services Administration (GSA). The arm of the federal government that handles procurement, the GSA has adopted a “Buy Clean” policy under President Biden’s Federal Sustainability Plan. King explains that because of the policy, “we’re going to be favoring low carbon materials over high carbon materials.” The biggest buyer of construction services in the country, King anticipates people will either use these low-carbon materials or lose business.

A self-proclaimed policy geek, King also helped establish what he says is “the world’s first climate-friendly building code to [reduce] the embodied [carbon] emissions from concrete.” King explains that concrete accounts for 8% of global carbon dioxide emissions. He also says that all the concrete projects he’d ever worked on were wasteful. “[It] was cheap insurance. Just put some extra cement in there… you don’t want to have a problem.” But to achieve 15×50, this insurance method doesn’t cut it anymore. Neither does traditional concrete.

That’s why King is in the middle of making a video called “How to Make Low Carbon Concrete.” Not only a hippy in the woods, author, engineer, and policy geek, King is also providing industry professionals with the knowledge needed to become more sustainable.

After receiving numerous calls asking for his technical advice, King realized that most engineering and architectural students aren’t learning sustainable building strategies. Even many professionals still lack the fundamental knowledge to build green. So, five or so years ago, King started to envision a website where people could go, like a library, to get information on green building materials.

King created BuildWell Media roughly a year ago to showcase work such as his low-carbon concrete video. An online resource of short videos and PowerPoint decks on sustainable design and construction, the content is accessible and digestible for both professionals and homeowners. While still in its early stages, King’s BuildWell Media, in collaboration with Stanford University’s Building Decarbonization Learning Accelerator, aims to support the 15×50 goal by providing the necessary information building blocks.

King’s drive and optimism surrounding everything from sustainable building design to policy and education make it easy to believe in nature and the future of the building industry. With knowledge, strict policy, the right materials, and determination, it just may be possible to store 15 gigatons of carbon in our buildings annually by 2050.