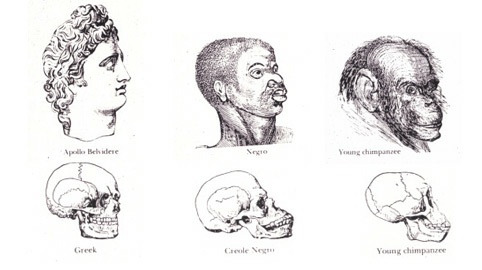

One of the first issues I want to unpack from my just completed seminar on race is the treatment of race, in part, as a topic of biological and scientific relevance. The history of scientific racism is the history of the origins and abuse of physical anthropology. It does not take much more than a brief glance at the works of such folks as George Glidden and Josiah Nott (1868 – see below) to realize the potential pitfalls of engaging race and biology simultaneously.

Why bother engaging race on biological and/or scientific ground? Why bother given the potential repercussions of reifying false notions of biological race? Why bother given that we know a social constructionist view of race is actually vastly more relevant for understanding most of the problems we see in the world surrounding racial inequality and racism? Why do I do it?

Treating race in biological terms is not intended to deny the significance of a social constructionist view of race or even the primacy of such an understanding of race. Rather, it is meant to recognize that some of the most pernicious and dangerous characterizations of race come from a poor understanding of the relationship between explicitly biological variation and the false association of such differences with race. Race is a social concept, created and re-created on a daily basis in the performance and perception of individuals and groups of individuals. But patterned biological variation is also a reality, structured by human evolutionary history and the web of ancestry and biologically relevant experience each of us carries.

One of the readings that was presented was Imani Perry’s (2011) recent book titled, “More beautiful and more terrible: The embrace and transcendence of racial inequality in the United States.” In the book, Perry presents the concept of “correlational racism” (pp. 16-17):

In truth, the racism we see in the United States is more appropriately called “correlational” racism, in which disfavored qualities or, for preferred groups, favorable qualities are seen as being highly correlated with membership in certain racial groups and dictate the terms upon which individual members of those groups are treated, as well as the way we evaluate the impact and goals of policy, law, and other community-based decision making.

This kind of correlational racism helps explain why biologically-based racism remains so persistent and dangerous. Biological differences (in health, appearance and other aspects of phenotype) are highly pervasive and lend themselves readily to the kind of correlational relations Perry describes. This is particularly true if, like me, you believe some of the literature on childhood development and concepts of race. I have been heavily influenced by the work of Larry Hirschfeld which suggest that children at a very young age have already developed notions of people belonging to different “natural kinds”–the kind of cognitive categorization that lends itself to unsupported inferential judgement…also known as prejudice. That we are prone to be prejudiced need not be bad, but that we live in a massively racialized world as a result of historical and contemporary practices around the social concept of race makes this tendency particularly problematic.

Part of my presentation at our seminar was trying to put this paradox of race–the simultaneous false use of race to explain biology (at least in simple terms, the work by Clarence Gravelee provides a great example of how racism, the cultural manifestation of race, can shape biological patterns) and the observable reality of patterned biological differences–in a historical framework drawn from the development of genetic technology.

The two pillars of anthropology’s rejection of race as a biological concept are Frank Livingstone’s famous statement that “there are no races, there are only clines” (1962) and Lewontin’s observation that the genetic variation within human populations is vastly greater than the variation that serves to distinguish between populations or racial categories (1972). Both of these statements were made on the basis of genetic variation, assessed indirectly through protein variation within and between populations. However, while the serious engagement of race as a question of biology ended in physical anthropology with these papers, our characterization of human biological differences did not end with Livingstone and Lewontin’s collective rejection of the biological concept of race. The subsequent development of increasingly sophisticated technologies to directly assess genetic data–direct sequencing by the early 1980s, the human genome project and subsequent development of human genomics in the first decade of the 21st century, and the massive influx of genomic data brought about by next-generation high throughput genomic sequencing platforms–have dramatically refined our ability to assess biological variation at the genetic level.

Livingstone’s claim about patterns of clinal variation (i.e. independent, gradually changing frequencies in traits, rather than discrete clusters) is true for the kinds of phenotypic characters subject to geographically associated natural selection that were available to him at the time, but does not accurately describe patterns of neutral genetic variation. Lewontin’s description of the pattern of genetic variation within and between human populations remains correct at the superficial level, but fails to acknowledge the many small parts of the genome that do not fit this pattern but which are observable with modern genetic technology. The limitations of Livingstone and Lewontin do not undercut the claim that race is fundamentally not biological, but the pattern of variation available to us today is vastly more complex than that simplified account. With the ability to sequence a genome in its entirety very quickly and at very low cost, we can see and quantify very small aspects of human variation.

You might imagine this as the difference between looking at the moon with your naked eye versus looking at it with a massively high powered telescope. With your naked eye, the moon is spherical with slight dimpling patterns characterizing its surface. With a high-powered telescope, the moon is still spherical, but its surface can now be seen in immense detail, down to the level of individual rocks and piles of dust. With the genome, we are looking at grains of sand on the surface of the moon. To say its round and dimpled is not wrong, it simply ignores a lot of the more subtle variation available to us. This subtle variation is real. And in the case of subtle genomic variation, it is patterned on the basis of human evolutionary history and individual patterns of ancestry. One could still choose to reject race’s relationship to biology and focus entirely on the social constructionist view of it and do quite well in developing a rich understanding of the topic. But, such an approach is going to fail to engage all of those people who see this complex pattern of biological variation and immediately ascribe it to race. The mere presence of that data is going to seed the ground for a continuous revival of a biological notion of race.

I teach about race through the lens of biological variation because my goal is to get students aware of the complex set of factors that shape patterns of biological variation instead of falsely assuming such differences are the result of race. I try to get my students to understand that what we speak of as race is a complex and ever-changing concept that is, at times, informed by patterns of biological variation. I try to develop an understanding in my students of the differences between race and biology on scientific grounds so that when confronted with a scientific study showing differences in health outcomes or physical features or genetic traits, they are equipped to understand those data in the framework in which those data were produced rather than simply reject them on the grouds that race cannot be biology.

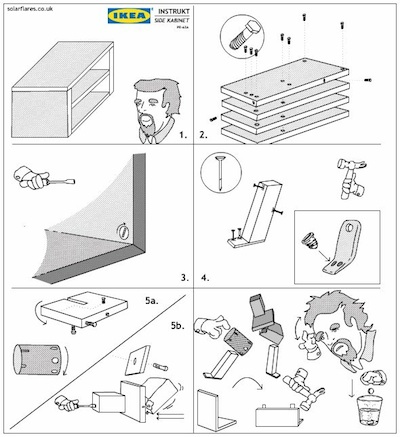

Part of what came out of the discussion the past two days was the disconnect between my own understanding and use of the term “biology” and how that term was perceived by several of my social science colleagues. For me, and this is how I teach the concept in my classes, “biology” is a complex, structured and dynamic set of interactions. For some of my colleagues, it was clear that “biology” was more or less synonymous with “genetics,” which was itself viewed as representing a discrete and deterministic system. DNA is often described as “the blueprint of life.” Such a metaphor can easily be seen as supporting this simple and deterministic vision of biological processes. After all, a blueprint dictates what a structure is to become. But I think this is an overly simplified understanding of what a blueprint is, and therefore leads to false notions about the nature of biological processes. What a blueprint really does is dictate a series of stratified interactions. I often use this caricature of a set of IKEA instructions to illustrate this point.

The instructions pictured do not make inevitable the final form of the bookshelves, rather they set up a series of interactions between person and tool, tool and materials, integrated parts with each other, that collectively will determine what the final end product looks like. Within these interactions are spaces for individual variation, environmental feedback and a host of other factors to enter in. The same is true for DNA’s role as the blueprint of life. It may serve as a basal template (although obviously there are processes that occur at levels below DNA), but one that sets up a whole host of downstream genetic, epigenetic, developmental, environmental and behavioral feedback systems and interactions.

There is a fear that in ceding any biological ground to understandings of human differences we are setting ourselves up for a deterministically-driven, biological racism. I do not think it has to be that way…if and only if students are taught to properly regard how biology works.

The real challenge as I see it is in figuring out how to conceptualize patterns of human biological difference in non-racial terms. This is one of the constraints I alluded to in my previous post. As an alternative to “race” you will frequently see people talk about “ethnicity” or “ancestry,” but compare the usage of those terms and there is really distinction without a difference. On one side, there is the difficulty of escaping the two-pronged reality of historically embedded (though not fixed) racial categorizations and the cognitive drive for categorical taxonomies that reduce the complexity of variation in the world around us into reductive, operational terms. On the other hand is the reality of a pattern of biological differences that continually indirectly inform such structural issues.

Eliminating the racialized structural feedback from biological variation would necessitate denying the existence of biological variation (something we do the opposite of by producing increasingly fine-grained genetic data) or finding an effective alternative way of describing such variation in non-racial terms. Eliminating the value-based judgements (racism) correlated with human biological differences necessitates doing away with historical patterns of inequality we are continually exposed to in the world around us. Ultimately, it would be wonderful to development socially tractable genetic categorizations that eschew racialized assessment. Perhaps the eventual spread of individual genomic data into social media will make this possible, but for the present, I choose to try and navigate the fine line between denying the reality of biology and denying the primacy of culture.

*****

1. F. Livingstone (1962) “On the non-existence of human races” Current Anthropology 3(3):279-281.

2. R. Lewontin (1972) “The apportionment of human diversity: Evolutionary Biology 6:381–398.

3. I. Perry (2011), More Beautiful and More Terrible: The Embrace and Transcendence of Racial Inequality in the United States. NYU Press. ISBN: 0814767370

intrigued about your comment about clinality and neutral variation. can you say more in a technical sense? i.e., are you alluding to some of noah rosenberg’s recent work?

Razib,

Rosenberg is certainly one of the people whose work I am referring to. Specifically I am thinking about something like figure 6 from the 2005 paper by Rosenberg et al. “Clines, Clusters, and the Effect of Study Design on the Inference of Human Population Structure”

-Adam

Great post, Adam – thank you for writing this up! I think “race” is the probably the most important topic physical anthropologists can teach to our undergraduates and to the general public. Humans are biocultural organisms; our field is uniquely positioned to weigh in on the race issue. And what we have to say about it can be enormously useful. The relevance of the topic needs no elaboration. If nothing else, when I tell people what I do, I get asked about race far more often than cavemen, ha.

I’m not sure whether I try to “navigate the fine line between denying the reality of biology and denying the primacy of culture” when I teach race. Rather, I use specific examples to illustrate how understanding both patterns of human biological variation and human cultural variation results in a more productive understanding than either can by itself. In my lectures I like to use two immediately accessible broad categories: healthcare/medicine and sports. For the former, topics like BiDil, the recurrence of rickets in the UK, Tay-Sachs, lactase persistence, and so on resonate well with audiences. For the latter, I have a lecture called “Why the NBA is mostly black guys and the NHL is mostly white guys” that is immediately gripping and doesn’t let go.

I think the most important realization that came from Livingstone’s, Lewontin’s, and other pioneers’ work isn’t just the clinal nature of human genetic variation – it’s that these variations are rarely concordant. Race is an easy and seductive way to approach many issues in life – and it’s wrong (not just in a moral sense, but also in a biological sense). Reality is far more complex and detailed than crude, anachronistic generalizations. The more we’re learning about genetics thanks to faster, cheaper, more accurate technology, the more interesting and useful these details will become.

What I am trying to get at with that statement, Zach, is basically how I conceptualize a biocultural approach to race, which is pretty much who you are describing. I respect the non-concordant aspect of Livingstone’s observation, which is what I was alluding to with my use of “independent” distributions of traits.

Thanks for the interesting post. One of my favorite activities to do when teaching about race is, after discussing the social history of race in America and the reality of clines and geographic variation, I give the students clickers and go through a slide show, making they select a race for each person they see. I use lots of mixed heritage folks and people from areas that are not traditional immigration hot spots. As we go through students have a hard time classifying a lot of these folks, and we talk about the traits they use to make their racial decisions. It is then that they realize how much they also use cultural context to make their racial categories. Since they can’t hear how a person speaks, or know their social status, they try to use clothing, haircuts/facial hairstyles and objects in the background to make their racial decisions. Then I tell them which region of the world the person is from, and highlight some of the biological variation they can see, and how it is similar or different to people in other regions. Students seem to enjoy it, and I think it helps them understand how complex race really is.

This is really great stuff, and I hope it gets widely read. Particularly nice telling of the Livingstone-Lewontin importance but later genetic fine-tuning. Unfortunately far too many have not updated since Livingstone-Lewontin and just assume it was all cleaned up back in 1972.

Also particularly great description of how to not reduce biology to genetics and deterministic instructions. I think that’s part of what the current Dawkins versus Wilson tussle is about. But I’d also like to point here to Tim Ingold’s work–what you’ve written about the relationship between instructions and trying to build or grow something is very reminiscent of his chapter, Of string bags and birds’ nests (2000).

I do have one quibble, which relates to an idea I’m working through for what I hope is a longer piece. It’s when you say that “The mere presence of that data is going to seed the ground for a continuous revival of a biological notion of race.” It is not the presence of the data that revives the biological notion of race–it is instead what you say later, the “historical [and actual] patterns of inequality.” In other words, it is a political agenda which seeks to explain away, justify, or argue against any attempts to address those patterns of inequality–that political agenda will inevitably return to recycle biological notions of race, regardless of the presence (or absence) of data. I’d be curious to know what you think…

Thank you again–really important piece.

Thanks for passing along the link to Ingold’s work…he is someone I really need to read more of.

I think you are also correct in clarifying my comments about the persistence of the biological race concept. I think you are absolutely correct that there are both political and social motivation to push notions of biological race, rather than socially and politically mandated inequality. This is definitely the area that some of my colleagues were pushing back from. Why bother talking about the biology of it all when much more progress could come about from putting the spotlight on the political, legal, economic and social policies that actively maintain the status quo. And it is a point that I will continue to work over in my own head, because it has an awful lot of merit.

Hi Adam,

Thank you for the thoughtful response. I don’t think I would agree with your colleagues. It is the responsibility and strength of anthropology to tack between biology, genetics, social aspects. Keep up the good work!

Jason

Really excellent post on multiple fronts, Adam. I particularly appreciate where you mention how non-biologists equate ‘biology’ with genetics/fate/determinism. This is a big divide, and something to watch out for when communicating with the public about biology. Thanks for sharing this.