Nature released the latest Australopithecus sediba paper today, this one attempting to reconstruct the diet of sediba based on phytoliths extracted from the dental calculus of two individuals, the carbon isotope composition based on laser ablation isotope ratio mass spectrometry, and finally an analysis of dental microwear. The paper is multi-authored and involves the collaboration of specialists across all three of these areas of analysis.

Before I get into the details of the paper it should be noted that based on gross morphology, the striking thing about the published Australopithecus sediba dentition and overall masticatory apparatus is its gracility. Consider the mock-up image below, showing Dmanisi 2735 (the sub-adult mandible from Dmanisi) alongside UW88-8, one of the mandibles from Malapa.

The images are in approximate scale (nothing I’d want to take a measurement off of, but visually pretty accurate), making clear the similarities in gross size between the molars of the Dmanisi and Malapa individuals. There are differences in the structure of the teeth (e.g. the Malapa molar form appears much more “bulbous” than that of Dmanisi), but the overall size and shape are quite similar. Not necessarily a comparison you would reconstruct dramatically different diets for the two individuals.

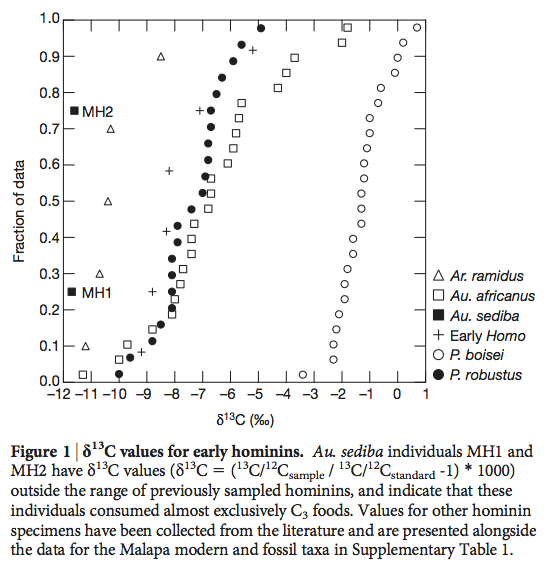

And yet, the results of this paper seem to suggest that sediba was eating a peculiar diet in comparison to what we know about other Plio-Pleistocene hominins. The phytoliths suggest that while the environment featured a lot of C4 grasses, sediba was eating almost exclusively C3 plants. The stable isotope analysis supports this conclusion. The isotopic composition supports this conclusion, as the two Malapa individuals tested show a strong C4 signal, most similar among studied hominins with Ardipithecus ramidus, an early Pliocene hominin from East Africa (and one that has been argued to occupy a fairly forest-heavy environment). The dental microwear is a little more difficult to dissect because it is quite variable, but the Malapa material show similarities in complexity and directionality of wear marks with another South African hominin, P. (Au.) robustus.

It will be interesting to go into the details in more depth (hello, online supplemental information), but the initial appraisal continues to raise more questions about sediba than it answers. These individuals continue to defy a simple placement within existing taxonomic frameworks for Plio-Pleistocene hominins. Depending on what aspects of these specimens you focus your attention on (cranio-dental variation, post-cranial functional morphology, diet, habitat, etc.), you can make an argument for or against affinities with just about any potentially related hominin taxa. My guess is that, at least to some degree, these results make the argument for sediba being a predecessor to Homo less likely, but that depends on what role you see for diet in the speciation process leading to Homo.

The good news is that (I think) the article is open access. So read it an enjoy.

UPDATE:

Science Daily has a news story up on the research, featuring a number of quotes from Texas A&M anthropologist and Malapa team-member, Darryl de Ruiter:

“This gives us a very clear picture of their diet, and it was surprising. It shows that they ate more fruits and leaves than any other hominin fossil ever examined, more like what a chimp might eat. There was no evidence of them eating native grasses of the area at that time, which is what we see in other australopiths in the region.”

Erin Wayman, blogging at Hominid Hunting, also has a post up on the paper

UPDATE 2: Kate Wong provides her take at Scientific American

*****

1. Henry, A. G., P. S. Ungar, et al. (2012). “The diet of Australopithecus sediba.” Nature advance online publication. doi:10.1038/nature11185