This past Spring I published a paper, together with Milford Wolpoff, on the early evolution of our genus, Homo. The paper had several inspirations, independent of my own research in this arena associated with my work at the Lower Paleolithic site of Dmanisi. First, Suwa, et al. (2007), published a paper several years ago in which they conclude there is no evidence of Homo habilis and Homo erectus co-existing in the deposits of the Turkana Basin. Rather, all of the identified habilis specimens appear to pre-date the erectus remains, making a linear relationship between the two sets of remains possible. This idea is hardly new. Indeed, our other starting point was the original debates between Robinson and Tobias regarding the Olduvai remains from the 1960s. Regarding this earlier material, Robinson said:

…the Bed I [Homo habilis] material may represent an ad- vanced form of Australopithecus and the Bed II specimens an early H. erectus and at the same time the latter may be a lineal descendant of the former (Robinson 1966, p. 123).

Here is where Dmanisi comes into play. Dmanisi sits, chronologically, right in the middle of the rich deposits from Turkana and Olduvai, while providing the best single locality view of early Homo variation. Why not expand the null hypothesis of Suwa (2007) to the larger, more inclusive sample including Dmanisi. So that is what we did.

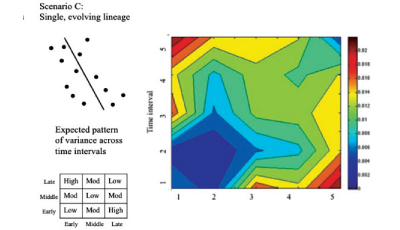

I don’t want to recapitulate the entire paper, but basically we examine the pattern of variation created by pairwise sampling as much of the fossil record from his time period (~1.9-1.5 MYA) as possible, attempting to reject a single, evolving lineage model. We fail to do so, while demonstrating that our approach can discriminate between even meager samples of Homo/robust Australopithecus. We fail to reject the null hypothesis, suggesting that despite the much expanded fossil record for this time period, the single lineage model remains the parsimonious explanation (based on our approach).

As it turns out, I am glad I did not blog on this earlier (despite plans to do so), because the paper has generated some response. Jeremiah Scott has a paper in press at Evolution responding to the paper (our reply is also forthcoming), and Adam Gordon & Bernard Wood mention the paper in an in press publication in the Journal of Human Evolution. This response is not surprising. Our argument is a bit heterodox. But more importantly, we published our complete data set with the publication, the largest available cranial data set for early Homo anywhere in publication. We wanted people to respond. How else does science work?

A few other points I wanted to raise about our paper. An important, but easily overlooked, part of our paper is the formulation of our hypothesis as an evolving lineage. This might sound matter of fact, but it is actually a rarely acknowledged approach in paleoanthropology to compare fossil assemblages spanning (hundreds of) thousands do years, with museum collections of primates and humans that span a few decades. This is not necessarily an insurmountable problem, but it is an implicit assumption about how we construct hypothesis tests that makes tests of evolution (i.e. changing patterns of variation) difficult. We are not testing a static model of variation, but rather one that changes across the time period we study.

Finally, we prioritize sample size over sample quality in our analyses. Our approach is multivariate, but not a traditional multivariate approach that utilizes a variance/covariance matrix generated from our sample. The nature of the fossil record from this time period (and most others), means that there are too many missing measurements and too many fossils lacking comparable elements to generate any kind of sample size (either in measurements or in specimens) for a traditional multivariate approach. Were we to take such a view, we would end up comparing only the very few well preserved specimens, utilizing only the very few measurements that are represented on each of them. We think the less preserved fossils matter. They do not preserve as much information as the better preserved specimens, to be sure, but given the data constraints within our field, an effort should be made to include them within the basic evolutionary models we construct. So that is the approach we take.

I am of course biased, but I happen to think the origin of the genus Homo is the most exciting current area of research in paleoanthropology. The evolutionary transitions that characterize the emergence of Homo from Australopithecus set the stage for the pattern of human evolution that develops in the Pleistocene. I hope our paper will continue to generate responses, both pertaining to our conclusions and the approach we take to reach those conclusions.

A SINGLE LINEAGE IN EARLY PLEISTOCENE HOMO: SIZE VARIATION CONTINUITY IN EARLY PLEISTOCENE HOMO CRANIA FROM EAST AFRICA AND GEORGIA

Adam P. Van Arsdale and Milford H. Wolpoff

ABSTRACT: The relationship between Homo habilis and early African Homo erectus has been contentious because H. habilis was hypothesized to be an evolutionary stage between Australopithecus and H. erectus, more than a half-century ago. Recent work re-dating key African early Homo localities and the discovery of new fossils in East Africa and Georgia provide the opportunity for a productive re-evaluation of this topic. Here, we test the hypothesis that the cranial sample from East Africa and Georgia represents a single evolutionary lineage of Homo spanning the approximately 1.9–1.5 Mya time period, consisting of specimens attributed to H. habilis and H. erectus. To address issues of small sample sizes in each time period, and uneven representation of cranial data, we developed a novel nonparametric randomization technique based on the variance in an index of pairwise difference from a broad set of fossil comparisons. We fail to reject the hypothesis of a single lineage this period by identifying a strong, time-dependent pattern of variation throughout the sequence. These results suggest the need for a reappraisal of fossil evidence from other regions within this time period and highlight the critical nature of the Plio-Pleistocene boundary for understanding the early evolution of the genus Homo.

*****

1. Van Arsdale, A. & M. Wolpoff (2012) A single lineage in early Pleistocene Homo: Size variation continuity in early Pleistocene Homo crania from East Africa and Georgia. Evolution 67-3: 841–850 DOI: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01824.x

2. Suwa, G., B. Asfaw, Y. Haile-Selassie, T. D. White, S. Katoh, G. Wolde Gabriel, W. K. Hart, H. Nakaya, and Y. Beyene (2007). Early Pleistocene Homo erectus fossils from Konso, southern Ethiopia. Anthropol. Sci. 133–151. DOI :10.1537/ase.061203

3. Robinson, J. (1966) The distinctiveness of Homo habilis. Nature 209:957–960.