Yesterday I was asked to take part in a roundtable discussion on “How to be a good ally” at this year’s upcoming AAPA meetings, organized and hosted by the Physical Anthropology Women’s Mentoring Network. So I was feeling good about myself…but also a little nervous, because one of the favorite things I have read about being an ally is this:

20. Finally, if you do all of the above, don’t expect a cookie. Your efforts may go unacknowledged or even unrecognized much of the time. Keep at it anyway, because you’re not out to get special recognition. You’re doing it because it’s the decent thing to do.

The above is taken from a great list from the blog, “Tenure, She Wrote” (this is also a recommended piece on the topic from the same blog).

And then today, this story comes out in Science, reported by Michael Balter:

Loudly, and apparently without caring who heard her, a research assistant at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City charged that her boss—noted paleoanthropologist Brian Richmond, the museum’s curator of human origins—had “sexually assaulted” her in his hotel room after a meeting the previous September in Florence, Italy.

It is important to read the full piece, which includes many more details. And this story, of course, comes after many, many, many similar stories (Jennifer Raff has some of the links).

So, with a lot of thoughts already going through my head about my experience as an ally, today seems like an important day to be an ally. So here are a few of my thoughts on the subject.

1) Listen more, talk less…

Writing this post seems contradictory to this message, but as a general rule of thumb, white guys already established in positions like me should talk less and listen more. It is important to acknowledge the reality of the stories people share, stories that are likely beyond our own range of experience (or even beyond the range of possibilities for our experience). Rather than assuming we know…assume we can’t possibly know.

2) …but stand up when necessary.

At the same time, our status also often affords us greater ability to vocally and stridently address injustices when we see them. Be willing to make your voice heard (after you have listened).

3) Embrace being an “anthropologist”

This one is more specific to us anthropologists…but within my own community of biological anthropology, there is a common tendency to disparage the broader collection of our field. That is a mistake, and one that has widespread negative consequences for our discipline. The social sciences, and I would say anthropology in particular, have a lot of outstanding research on the realities of racism, sexism, classism, systems of power, inequality, and the liminal experiences of “the field” that we should all embrace, not disparage.

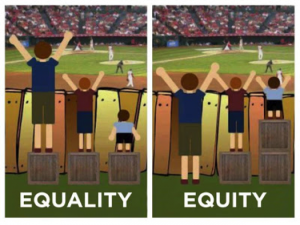

4) Familiarize yourself with the difference between equity and equality

I’ll let this picture do the heavy lifting on this one.

This issue applies across the range of our professional duties. One of the places I find it most useful to keep handy is the classroom. Our students come to our classes with a wide range of backgrounds and skills at engaging with institutional practices. Treating all of our students “equally” inevitably reinforces inequality. Recognizing this, and being wiling to reach out and actively work towards equity in our classrooms is an important responsibility to our profession.

5) Be vigilant of bias in our professional activities

The most basic aspects of our profession are often seen as mundane activities that require little special awareness. Writing letters of recommendation, organizing panel discussions, engaging with collaborators, etc. Despite their mundane nature, these activities form the backbone of our professional field. And in all of them, unconscious bias has ubiquitous effects on diversity.

So far all of the above is pretty easy. Most of it can basically be summed up as, “be a decent guy.” Here is where it gets harder.

6) Recognize that you are probably mediocre

Wait? What! But I am an established and well-regarded ________! I have publications! Grants! A title! And for all of those things, our path was likelier made easier by the unconscious and conscious biases of those around us. Our students evaluate us better for the same work. Our employers value us more for the same work. Our colleagues recognize us more for the same work. All of which means we are far more likely to be mediocre–in our thinking, our writing, our scholarship–than those around us who don’t receive such benefits. This is hard. I am not immune to the impostor syndrome, so acknowledging not the potential, but the likelihood, of my own mediocrity is hard. But it is important. It opens my eyes more fully to the work, ideas, and efforts of all of my colleagues. It motivates me to try to work towards not being mediocre, which betters the profession as a whole.

7) Be willing to make real sacrifices

There is a corollary to the above point that probably hurts even more. Expect less of everything you are used to getting. There are many aspects of professional academia that are zero sum issues. If I have been granted more of the benefit of the doubt than my colleagues, I have probably also been given more benefits. And if you want to be an ally, acknowledging that means being willing to accept less. Think that conference panel is too male? Maybe it is you who shouldn’t be on it. Colleague getting paid less? Maybe some of that difference should come from you. And be willing to give up perhaps the most precious resource of all for an academic…time.

8) Recognize that you might be, or have been, part of the problem

It is tempting to read stories like the one linked above and think the problem is about identifying who are the assholes. If we could just identify the bad guys, we could fix the problem. There might truly be bad guys, but that presents a false view of our own culpability and capabilities. All of us are capable of doing good and bad things. The goal is to do more of the former, and less of the latter.