It’s easy to say that most people who think of archaeology and Crete think of the site of Knossos. Knossos is the most publicized and well-trafficked of the Cretan sides.

It’s only 5 km outside of the bustling city of Heraklion (a bus even runs there from the city) and the site has been well publicized by it’s discovery and recreation by Sir Arthur Evans. The site unlike others on the island is partially reconstructed to more closely resemble its appearance in Minoan times. But what’s of interest to me is the strong cycle of myths associated with the area. King Minos, his family, and the myths involving him are strongly associated with the site of Knossos and the surrounding area.

The origin story of Minos starts with his mother, Europa. The story goes that Zeus came upon her, gathered with her friends in a field and was struck by her beauty. He turned himself into a bull that moved amongst the girls, until Europa climbed on his back. Then he took off, carrying her across the sea to the island of Crete. He convinced her to lie with him then, promising her that a continent would be named for her and her children would be kings. Eventually, she gave birth to Rhadamanthys, Sarpedon, and Minos.

Minos went on to become king of Knossos, marrying Pasiphae a daughter of the sun (Helios). Poseidon sent a bull from the sea many years later as a sign of auspicious rite and for it to be sacrificed in turn to him. Minos was so caught by the bull’s beauty that he didn’t sacrifice it and instead replaced it with another bull, not as shiny and white. In order to punish him, Pasiphae was cursed with an unnatural lust for the bull and she convinced the palatial architect to create a decoy bull so that she could mate with him. This union brought forth the Minotaur – half man, half bull – then concealed within the Labyrinth of Knossos. He remained there until killed by the Athenian Theseus with the help of Minos’ daughter Ariadne.

Walking around Heraklion, there was plenty of evidence of this mythological past. Streets named after Pasiphae and Ariadne lead the way to the Heraklion Archaeological museum, and the image of the bull is present in everything from t-shirts to graffiti. The art we saw at the Heraklion museum supported this connection to the past: images of women exotically “Cretan” and sexually vibrant, and bulls everywhere. You could feel the old stories as you walked the halls and streets, echoing the people currently walking them.

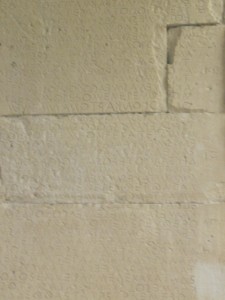

Yet this feeling wasn’t as present in Knossos. Perhaps this is partly Arthur Evans’ reconstructions. Here and there, bright red painted walls climb upwards mixed with Minoan ruins. The mix of old and reimagining tried to harken those times. The mythological past wasn’t part of Evans’ attempt to recreate the experience of being in the palace, nor did it seem evident in the more “untouched” areas of the ruins. Even the frescoes placed only harkened to a rare bull sighted. Where was the Labyrinth, even of myth? One sign was to look at the layers of ruins built on top of each other and the marks of the double headed axes about labrys. Perhaps it’s easier to imagine the mythological presence further away from these sites, rather than right on top of them.

Yet this feeling wasn’t as present in Knossos. Perhaps this is partly Arthur Evans’ reconstructions. Here and there, bright red painted walls climb upwards mixed with Minoan ruins. The mix of old and reimagining tried to harken those times. The mythological past wasn’t part of Evans’ attempt to recreate the experience of being in the palace, nor did it seem evident in the more “untouched” areas of the ruins. Even the frescoes placed only harkened to a rare bull sighted. Where was the Labyrinth, even of myth? One sign was to look at the layers of ruins built on top of each other and the marks of the double headed axes about labrys. Perhaps it’s easier to imagine the mythological presence further away from these sites, rather than right on top of them.