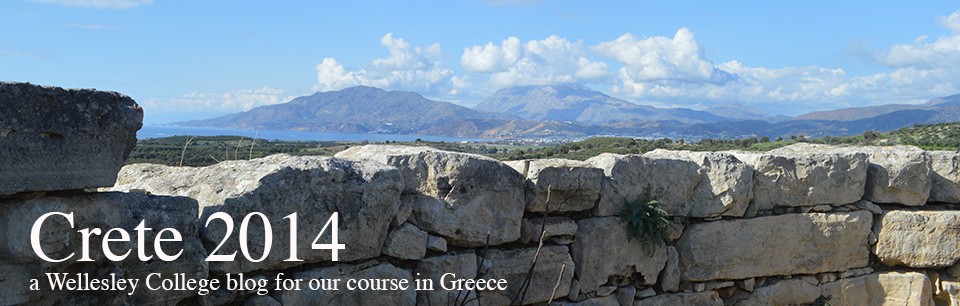

The Late Minoan I town of Gournia

Crete, as we have certainly seen, has a complex religious history. From the Mycenaean introduction of early Greek deity names, Crete saw a devotional shift with each foreign occupation. Wednesday we visited three sites – Gournia, Panagia Kera, and Lato – where we saw three examples of devotional spaces wherein these fluctuations are manifest.

Gournia was originally excavated by Harriet Boyd Hawes, a Boston native and Smith College graduate, in May 1901; Boyd, having been blocked from participating in pre-existing major excavations on Crete, used her fellowship to fund her own excavations, and thus became the first woman to direct a major field project in Greece as well as the first to speak before the Archaeological Institute of America. Boyd’s excavation of Gournia uncovered both a Goddess with Upraised Arms and a sacred stone, or baetyl.

A short drive away we reached a monastery that some have called the most important Christian monument on Crete, Panagia Kera. Built in the late 12th century, the façade is unassuming, straightforward, making the interior frescos all the more impressive. Each aisle has its own decorative programme: the south aisle is dedicated to Saint Ann and illustrates her and Joachim’s apocryphal story as Mary’s parents; the north is dedicated to Saint Antony and illustrates the second coming; the central is dedicated to the assumption and illustrates, among other scenes, the last supper, Herod’s feast, and men and women in hell.

The frescos date to the mid and late 13th century, which makes the presence of Saint Francis of Assisi rather remarkable, particularly because he hold such a prominent position on the east-facing pillar, visible immediately upon entering. It is easy enough to attribute this oddity to Crete’s contemporary occupation by Venice, but that all these frescos survived intact throughout the long period of Ottoman rule is not so easily explained. Molly Greene says of the occupation:

By the time the Ottoman navy appeared off the island’s northwestern coast in the spring of 1645, Catholic and Orthodox Cretans had lived together for almost five hundred years in a relationship whose complexity had no rival in the Greek East. The Ottoman conquest added another layer to this already complicated past by setting off a process of conversion to Islam that resulted in one of the largest Muslim communities in the Greek world. (A Shared World, 2002, Princeton University Press)

Maybe it’s survival is evidence of lenience, or maybe simply of Ottoman priority on prominent monuments in large cities, such as Chania and Heraklion.

The “Large Temple” at Lato

At Lato (the Dorian form of the more recognizable “Leto,” mother of Apollo and Artemis), we saw a prytaneion, an agora, and an Hellenistic temple, which for us is a canonical example of a “Greek temple,” unlike most of the benched temples with central hearths we’ve seen before. Lato’s inhabitation, however, dates as early as the LMIIIC on the acropolis, indicating, perhaps, that this site was sacred well before developments such as cut-stone altars and massive cult-statue bases, visible today.

From these three close-together sites we saw and felt the development and inter cultural exchange of devotional practices through Crete’s immense and equally rich history. We will likely never fully understand the identity of a G.U.A. or the function of a lustral basin, the reason Panagia Kera was left untouched, or to which deity Lato’s temple was dedicated, but these open questions add up to a distinct Cretan identity that we were lucky enough to taste.