Spread and Skepticism are the two metrics used by TwitterTrails to gauge the impact of a story on Twitter, and Twitter’s reaction to the validity or truthfulness of the story. This posting gives information of what these metrics are and examples of their usage.

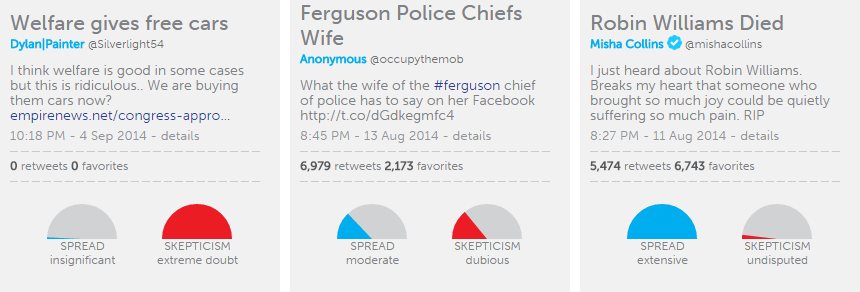

In this post we discuss the spread and skepticism of three claims, all of which are publicly viewable on TwitterTrails: the claim that people on welfare will receive free cars, the claim that the wife of the police chief in Ferguson wrote a racist post on her Facebook account, and the claim that Robin Williams died on August 11th, 2014.

Spread

Spread measures the visibility and impact of a story. The algorithm used to calculate spread is a variation of the h-index measure from Library Science, which captures how far reaching a story was, in terms of:

- depth: “were there tweets that received a great number of retweets?”

- breadth: “how many tweets received many retweets?”

Our use of the h-index algorithm is adapted from Library Science, where it is used to productivity and impact of someone’s scholarly publications. TwitterTrails uses the h-index metric to calculate the impact of a story. In our use, a tweet in the dataset of a story corresponds to a publication, whose retweets act like its citations. Retweeting a tweet increases its visibility (as retweeting effectively forwards a tweet to the retweeter’s followers), and gives it credibility (retweeting a tweet generally shows trust and agreement in the information presented in the tweet, see our paper Retweets Indicate Interest, Trust and Agreement for support of this claim).

Spread is measured as follows: TwitterTrails calculates the largest number x which represents the number of tweets that have each received at least x number of retweets.

To help understand this concept, and what it means (and does not mean) in use, consider the following examples:

- The claim that people on welfare will receive free cars: this story has a spread of 2, (on our scale, insignificant).

This means that, in our data, only 2 tweets received at least 2 retweets. One of those tweets received 5 retweets, while the other received 2. The spread captures not only the number of retweets received, but how many tweets received that number, so the fact that one tweet received 5 retweets does not increase the value. In addition, there are 15 more tweets which received only 1 retweet. In total, there are over 100 relevant tweets, the majority of which received no retweets at all. The spreading value of 2 does not represent how many tweets received less than 2 retweets. - The claim that the wife of the police chief in Ferguson wrote a racist post on her Facebook account: this story has a spread of 33 (on our scale, moderate).

This means that, in our data, 33 tweets received at least 33 retweets. There are tweets receiving more than 33 retweets: for instance, one which has 256 retweets. The spread does not count the number of tweets receiving less than 33 retweets; there are almost 1000 tweets which received at least 1 retweet, and of those over 100 of them received at least 10 retweets. It also does not count the total number of tweets collected; in this case, over 10,000, the majority of which have no retweets, or are retweets themselves (the spreading value only counts the original post). - The claim that Robin Williams died on August 11th, 2014: this is one of the most prolific stories which we have collected, with a spread of 444 (on our scale, extensive).

This means at least 444 tweets were retweeted 444 or more times. There are tweets in our data which have received thousands of retweets, some even tens of thousands. And there are over 10,000 tweets with at least 1 retweet; of those, almost 4,000 have at least 10 retweets; and of those, almost 1,700 have over 100 retweets. In total, we collected over 60,000 relevant tweets for this story, about two thirds of which are themselves retweets.

From these examples one gets a better idea of what the spread represents (and does not represent): it measures both the propagation of highest reaching tweets and the number of high reaching tweets, each of these two things constrained by the other. It does not reflect the one or two tweets with the most retweets, even those that have exponentially more retweets than the value of the spread. Nor does it measure how many tweets were collected. Although these numbers are interesting and meaningful, the spread is meant to give an overall picture of the impact of a story: how visible it was, as well as how many people were engaged in it.

Skepticism

Skepticism measures the prominence of doubt and mistrust in a story. Like spread, it uses our variation of the h-index. When calculating the spread, we measure the h-index over all the relevant data we collected for a story. Skepticism uses two subsets of the relevant data: those tweets which express doubt versus those that do not, in order to measure the presence and significance of skepticism being expressed.

The first step to calculating the skepticism is to identify tweets in which the author expresses mistrust in the validity of a claim, whether they are wondering if the claim is false or expressing that it is an outright lie. This is a difficult task, as doubt, disbelief, and mistrust can be conveyed in many ways, including the use of sarcasm, which are hard to detect, as well as taking into account tweets in different languages. For now, we employ a simple negation algorithm, which we have found works fairly well for identifying tweets which express skepticism.

TwitterTrails looks for tweets using the following 10 commonly used keywords to express doubt or disbelief:

hoax, fake, doubt, false, scam, untrue, mistake, unreal, bogus, mislead

See the section Detecting Doubt at the end of the post for a longer explanation and examples of how this algorithm works.

Calculating Skepticism

To calculate skepticism, we calculate the h-index (as defined the previous section) of tweets expressing doubt (as opposed to the spread of a story, which calculates the the h-index of all the tweets in the story), and compare it to the h-index of those that do not. Skepticism is a ratio of these two values. A value greater than 1 means that tweets which express doubt have spread further than those which express implicit belief in the claim, in so much as they do not question the validity of the claim in the tweet.

The skepticism for the three example stories are as follows:

- The claim that people on welfare will receive free cars: this story has a skepticism of 0.5 (on our scale, dubious).

The tweets which express doubt have an h-index of 1 in this story, and tweets that do not have an h-index of 2. So, the story has a skepticism of 0.5, which we have found to be a fairly high value. The tweets which express doubt spread about half as far as those that did not, though in the end neither spread very much (remember, this is a very low profile story, with an overall spread of only 2).

The tweets which express doubt have an h-index of 1 in this story, and tweets that do not have an h-index of 2. So, the story has a skepticism of 0.5, which we have found to be a fairly high value. The tweets which express doubt spread about half as far as those that did not, though in the end neither spread very much (remember, this is a very low profile story, with an overall spread of only 2). - The claim that the wife of the police chief in Ferguson wrote a racist post on her Facebook account: this story has a skepticism of 0.27 (on our scale, dubious).

This story has a much higher spread than the previous story (33 compared to 2). The tweets which express doubt have an h-index of 9, those that do not have an h-index of 33, which results in a ratio of 0.27. This is lower than the last story, but still fairly high. In this case, the claim is again false. Although the Facebook post that is being shared was real, the woman who wrote it was not the police chief’s wife. - The claim that Robin Williams died on August 11th, 2014: this story has a skepticism of 0.03 (on our scale, undisputed).

This is one of the highest profile stories in our database, with a spread of 444. The h-index of tweets expressing doubt in this claim is 12, while those that do not have an h-index of 443. Although this has the highest h-index of tweets expressing doubt, it has the lowest ratio: 0.03. When a story has a greater spread, the tweets that express doubt on the claim have a greater audience and a greater chance to be retweeted. This claim was true, and many of the tweets expressing doubt express more of a hope that the story is false than strong conviction that it is (after all, there are many celebrity death hoaxes, including one about Robin William’s shortly before he died).

This is one of the highest profile stories in our database, with a spread of 444. The h-index of tweets expressing doubt in this claim is 12, while those that do not have an h-index of 443. Although this has the highest h-index of tweets expressing doubt, it has the lowest ratio: 0.03. When a story has a greater spread, the tweets that express doubt on the claim have a greater audience and a greater chance to be retweeted. This claim was true, and many of the tweets expressing doubt express more of a hope that the story is false than strong conviction that it is (after all, there are many celebrity death hoaxes, including one about Robin William’s shortly before he died).

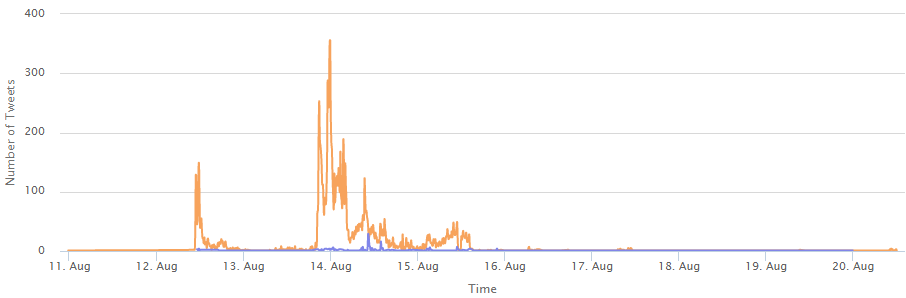

Two of our three examples are false; however in none of them do tweets expressing doubt spread further than those that do not. There are actually very few stories which we have collected where the negation of a claim spreads farther than support of the claim. It is usually after a false claim picks up steam that people begin to doubt it or realize that it is false. This doubt expressed en masse will slow down and eventually stop support of the claim, but very infrequently will it spread as far as the initial support.

The following graph compares tweets expressing doubt to those that do not in the story investigating the claim that the wife of the police chief in Ferguson wrote a racist post on her Facebook account. The number of tweets which do not express doubt about the claim are in orange, and those that do express doubt are in purple. You can see that there is a much higher spike in activity for non-doubting tweets, but that activity starts to taper off after the doubting tweets begin to peak.

Because of this, the spread of a story tends to affect the skepticism somewhat, and vice versa. Some false claims never gain enough traction on Twitter for people to notice and debunk them. And in general, false claims do not spread as far as true claims (for more discussion on this, view our blog post False rumors do not spread like True ones). From our experience, skepticism values greater than 0.25 tend to be very strong indicators of a claim being false.

In a future blog post, we will discuss a classifier which uses these two measures in order to label stories about claims as either true or false.

Detecting Doubt

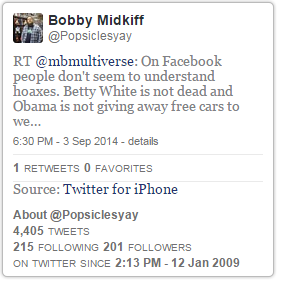

We mentioned that TwitterTrails looks for tweets using the following 10 commonly used keywords to express doubt or disbelief: hoax, fake, doubt, false, scam, untrue, mistake, unreal, bogus, and mislead.

We have found that for most of the English tweets, these keywords work well. In about 20% of the cases, however, these are not enough to capture the majority of tweets: sometimes they miss tweets which should be counted, and sometimes they capture too many tweets, when people are using these words but without the intention of expressing doubt. To combat this, the algorithm can be customized on a story by story basis: words can be added or removed from this list, and words can also be added to a list so that their presence in a tweet excludes it from being counted.

We have found that for most of the English tweets, these keywords work well. In about 20% of the cases, however, these are not enough to capture the majority of tweets: sometimes they miss tweets which should be counted, and sometimes they capture too many tweets, when people are using these words but without the intention of expressing doubt. To combat this, the algorithm can be customized on a story by story basis: words can be added or removed from this list, and words can also be added to a list so that their presence in a tweet excludes it from being counted.

Consider the following examples of tweets which do and do not express doubt:

The claim that people on welfare will receive free cars

Not counted: “Just read that welfare recipients now even get free cars????”

Counted: “No, Welfare Recipients Aren’t Being Given Cars And Free Gas”

The claim that the wife of the police chief in Ferguson wrote a racist post on her Facebook account

Not counted: “WOW “@peculiarivy: wife of #Ferguson police chief says community is “feral”. RT @YourAnonNews Look at this crap”

Counted: The pic going around of #Ferguson police chief’s “wife” is bogus. That’s some random racist lady. Things are bad enough w/out fake rumors.

The claim that Robin Williams died on August 11th, 2014

Not counted: I’m honestly so sad about Robin Williams. Devastated. #RIPRobinWilliams

Counted: The Robin Williams death better be a hoax and that humble faced man better be sat sipping tea somewhere right now alive and well

Not counted: Here go ppl fake caring about Robin Williams death smh (although the word “fake” is in here, it is not used to express doubt)

Not counted: I am terribly sad to hear about the death of Robin Williams. One of my all-time favorite movies is Mrs. Doubtfire. How about you? (“doubt” appears in here, in Doubtfire, so “doubtfire” is used as an excluded word)