The following is a blog post that Eni Mustafaraj has recently published in The Spoke. We reproduce it here with permission.

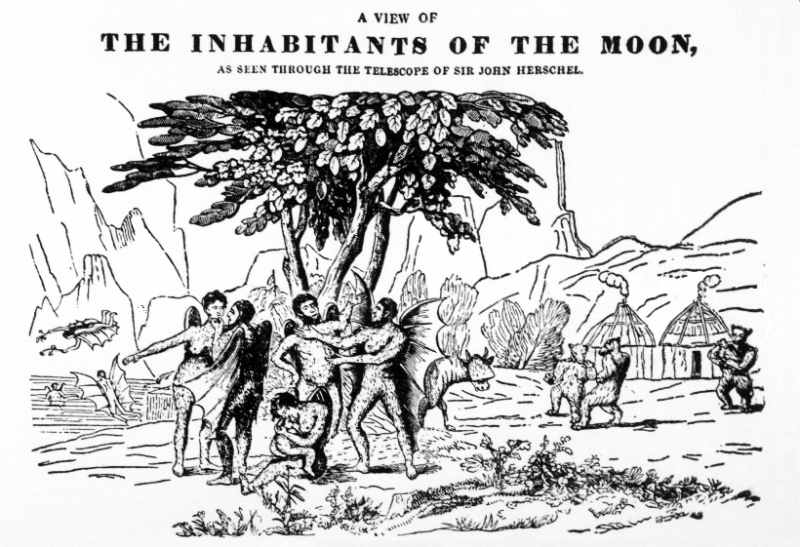

Fake news has always been with us, starting with The Great Moon Hoax in 1835. What is different now is the existence of a mass medium, the Web, that allows anyone to financially benefit from it.

Etymologists typically track the change of a word’s meaning over decades, sometimes even over centuries. Currently, however, they find themselves observing a new president and his administration redefine words and phrases on a daily basis. Case in point: “fake news.” One would have to look hard to find an American who hasn’t heard this phrase in recent months. The president loves to apply it as a label to news organizations that he doesn’t agree with.

But right before its most recent incarnation, the phrase “fake news” had a different meaning. It referred to factually incorrect stories appearing on websites with names such as DenverGuardian.com or TrumpVision365.com that mushroomed in the weeks leading up to the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. One such story—”FBI agent suspected in Hillary email leaks found dead in apparent murder-suicide”—was shared more than a half million times on Facebook, despite being entirely false. The website that published it, DenverGuardian.com, was operated by a man named Jestin Coler, who, when tracked down by persistent NPR reporters after the election, admitted to being a liberal who “enjoyed making a mess of the people that share the content”. He didn’t have any regrets.

Why did fake news flourish before the election? There are too many hypotheses to settle on a single explanation. Economists would explain it in terms of supply and demand. Initially, there were only a few such websites, but their creators noticed that sharing fake news stories on Facebook generated considerable pageviews (the number of visits on the page) for them. Their obvious conclusion: there was a demand for sensational political news from a sizeable portion of the web-browsing public. Because pageviews can be monetized by running Google ads alongside the fake stories, the response was swift: an industry of fake news websites grew quickly to supply fake content and feed the public’s demand. The creators of this content were scattered all over the world. As BuzzFeed reported, a cluster of more than 100 fake news websites was run by individuals in the remote town of Ceres, in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia.

How did the people in Macedonia manage to spread their fake stories on Facebook and earn thousands of dollars in the process? In addition to creating a cluster of fake news websites, they also created fake Facebook accounts that looked like real people and then had these accounts subscribe to real Facebook groups, such as “Hispanics for Trump” or “San Diego Berniecrats”, where conversations about the election were taking place. Every time the fake news websites published a new story, the fictitious accounts would share them in the Facebook groups they had joined. The real people in the groups would then start spreading the fake news article among their Facebook followers, successfully completing the misinformation cycle. These misinformation-spreading techniques were already known to researchers, but not to the public at large. My colleague Takis Metaxas and I discovered and documented one such techniqueused on Twitter all the way back in the 2010 Massachusetts Senate election between Martha Coakley and Scott Brown.

There is an important takeaway here for all of us: fake news doesn’t become dangerous because it’s created or because it is published; it becomes dangerous when members of the public decide that the news is worth spreading. The most ingenious part of spreading fake news is the step of “infiltrating” groups of people who are most susceptible to the story and will fall for it. As explained inthis news article, the Macedonians tried different political Facebook groups, before finally settling on pro-Trump supporters.

Once “fake news” entered Facebook’s ecosystem, it was easy for people who agreed with the story and were compelled by the clickbait nature of the headlines to spread it organically. Often these stories made it to the Facebook’s Trending News list. The top 20 fake news stories about the election received approximately 8.7 million views on Facebook, 1.4 million more views than the top 20 real news stories from 19 of the major news websites (CNN, New York Times, etc.), as an analysis by BuzzFeed News demonstrated. Facebook initially resisted the accusation that its platform had enabled fake news to flourish. However, after weeks of intense pressure from media and its user base, it introduced a series of changes to its interface to mitigate the impact of fake news. These include involving third-party fact-checkers to assign a “Disputed” label to posts with untrue claims, suppressing posts with such a label (making them less visible and less spreadable) and allowing users to flag stories as fake news.

It’s too early to assess the effect these changes will have on the sharing behavior of Facebook users. In the meantime, the fake news industry is targeting a new audience: the liberal voters. In March, the fake quote “It’s better for our budget if a cancer patient dies more quickly,” attributed to Tom Price, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, appeared on a website titled US Political News, operated by an individual in Kosovo. The story was shared over 80,000 times on Facebook.

Fake news has always been with us, starting with The Great Moon Hoax in 1835. What is different now is the existence of a mass medium, the Web, that allows anyone to monetize content through advertising. Since the cost of producing fake news is negligible, and the monetary rewards substantial, fake news is likely to persist. The journey that fake news takes only begins with its publication. We, the reading public who share these stories, triggered by headlines engineered to make us feel outraged or elated, are the ones who take the news on its journey. Let us all learn to resist such sharing impulses.