Jerry Coyne, evolutionary geneticist at the University of Chicago and author of several biological texts as well as texts on evolution and faith, started an argument about the politics of the left and science in a post titled, “The ideological opposition to biological truth.” He begins:

One distressing characteristic of the Left, at least as far as science is concerned, is to let our ideology trump scientific data; that is, some of us ignore biological data when it’s inimical to our political preferences

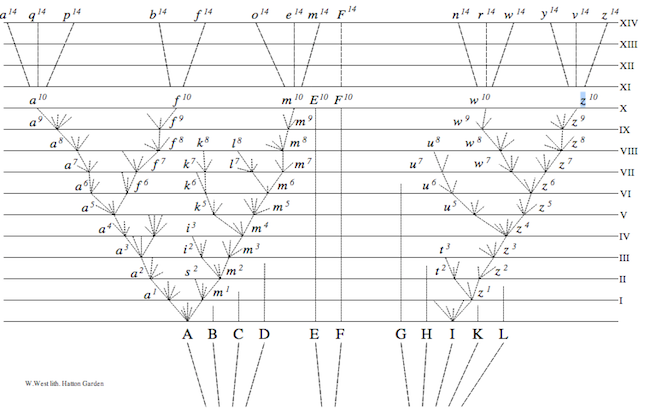

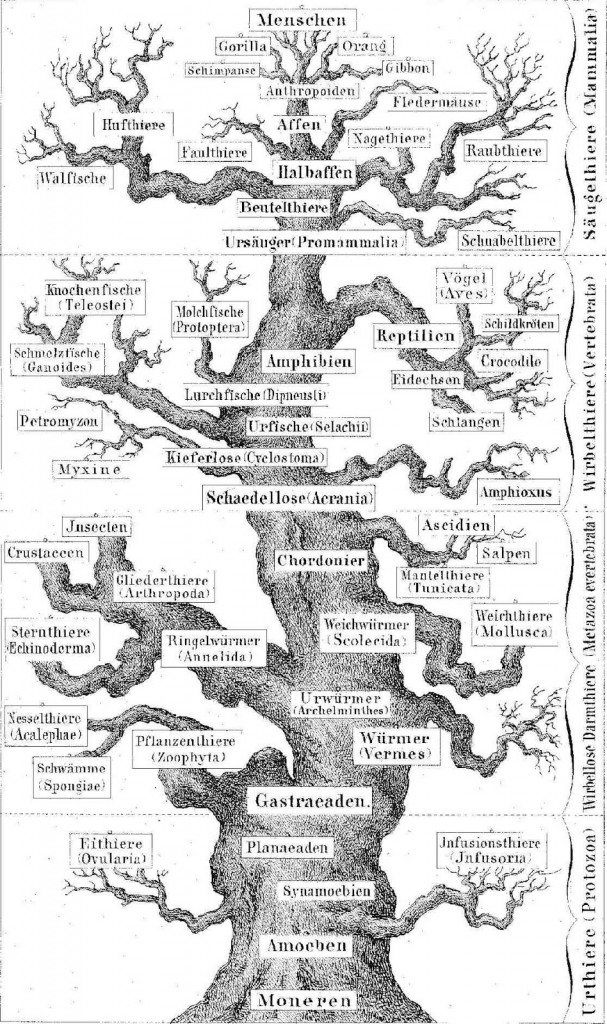

The proximate cause of his argument was a post from P.Z. Myers (a fellow biologist and blogger) about the primacy of culture over biology–specifically differential levels of testosterone in males–in explaining patterns of human violence. Coyne makes the argument that differences in male body size, relative to females, are a clear product of evolution and an aspect of biology, and are clearly not just correlated but also causal of aspects of male behavior, particularly elevated rates of male aggressive behavior. For example, among the apes, species of gorilla show a high level of male/female body size dimorphism and tend to operate in single (adult) male-multiple (adult) female social groupings. Chimpanzees have moderate levels of body size dimorphism (not unlike humans), and operate in complex social groupings that involve a varying presence of adult males and females. Gibbons and siamangs, which have essentially no body size dimorphism, tend to maintain long-term male/female pair-bonds as adults. Across these groups we observe differing levels and patterns of both male and female aggressive behavior.

Never miss the opportunity to post pics of Hylobates

Coyne makes the further argument that these characteristic differences between human males and females, as Coyne describes them, are almost assuredly the result of sexual selection. Coyne’s own evidence is largely summary descriptions, coupled with one research citation, a 2006 paper by biological anthropologist, Adam Gordon, on size and scaling of body size/skeletal size dimorphism in primates (Gordon, 2006).

In response, another biological anthropologist, Holly Dunsworth, pointed out the bias in Coyne’s perspective in a series of tweets, eventually collated in a post on the blog she co-authors (The Mermaid’s Tale), titled, “In Man’s Evolution, Women Evolve Too.” Dunsworth’s point is that in framing the narrative of human body size dimorphism strictly from the perspective of selection on male body size and male reproductive behaviors, we are obviously biasing ourselves towards male-centric hypotheses:

Not only is it absent, but selection on women’s bodies may be the driving force (if such a thing could be identified) and, yet, it’s as if women don’t exist at all in these tales except as objects for males to fight over or to fuck (but *thankfully* there’s that female choice!). Knowledgeable people aren’t objecting to facts, as Coyne suggests. They’re objecting to biased story-telling and its annoying and harmful consequences, which Coyne doesn’t acknowledge or grapple with in his piece.

Dunsworth’s extended twitter conversation was picked up and reported in a piece by Jesse Singal for NY Magazine (Not All Critiques of Evolutionary Psychology Are Created Equal).

These responses did not go unnoticed by Coyne.

Coyne fired off two more posts on his blog (“I get pushback on the sexual-selection theory for sexual dimorphism” and “The evolution of sexual dimorphism in humans: Part 2”) in which he doubles down on his original argument for human dimorphism being the product of sexual selection on male size and behavior and does not mince his words about Dunsworth’s post:

I conclude that Dunsworth knows nothing of my history of writing on evolutionary psychology and, further, is remiss in her own scientific approach, offering a story that’s amenable to her ideology because it allows females to evolve (mine does too!), and also a story that not only fails the empirical tests, but can’t predict the observations that sexual-selection theory can. Too, there seems to be more than a touch of intellectual mendacity in the way both she and Singal blithely ignore the supported predictions of the sexual-selection theory. Believe me, it’s more than “just a story.

This whole affair could be simply an argument about human sexual dimorphism in body size and behavior (more on that below), but it reflects a broader and almost assuredly more important issue about how authority and knowledge get constructed in science, as well as the public responsibilities of science. As someone who considers myself a scientist and the work I produce scientific, I am not an outside critic, but instead a stakeholder in science and scientific knowledge. How we, as scientists, account for our own responsibility in the kind of knowledge we produce is particularly critical at the current political moment, where facts and “truthiness” seem to stand on equal footing. And, it is worth noting, where ugly voices of intolerance have broad and important platforms.

How we represent evolution and our evolutionary past matters

Coyne’s rendering of a male-centric view is by no means an isolated event. At about the same time the dustoff between Coyne and Dunsworth was beginning, an exciting new discovery in paleoanthropology was announced. The finding, a set of previously unknown hominin footprint trails from the ~3.7 million year old site of Laetoli, Tanzania, was published in the journal eLife, complete with links to open access, downloadable 3D models of the footprints! (Masao, et al. 2016). These footprints appear to represent at least two individuals, including individuals with seemingly marked differences in body size. Indeed, the authors of that paper suggest that one significant aspect of their finding is that it might support the argument that Australopithecus afarensis (the presumed hominin in question) had substantial sexual size dimorphism. The subsequent media pickups of the research, however, featured headlines like, “Oldest early human footprints suggest males had several ‘wives’” (courtesy of The New Scientist).

Why is this a problem? First, “wives” are a social category, not a biological one. Second, the possessive verb “had” suggests a kind of ownership that implies both male domination and a degree of long-term pair-bonding (presumably culturally mediated) between reproductive mates. Third, the headline leaps from the data–in this case the footprint finds themselves–all the way to the most speculative inferences (not “facts”) of the publication, which are the implications of this find for our interpretation of hominin sexual behavior.

Now the gritty detail part. Why do I say this is the most speculative aspect of the find?…because understanding human size sexual dimorphism turns out to be quite complicated.

So why is understanding human dimorphism so complicated?

There are a couple of big reasons. The first is that when we look at the fossil evidence for human body size/skeletal size dimorphism in our evolutionary past, the evidence is incomplete. Not that there is not evidence. We have thousands and thousands of hominin fossils (we really do have lots and lots of human fossil evidence!). But arguments about characteristic differences between different categories of things, like males and females, in a fossil context, are particularly sensitive to issues of sample size. As the footprint story from Laetoli suggests, there is a long argument in paleoanthropology about the magnitude of size sexual dimorphism in early hominins, particularly based on fossil evidence of Australopithecus afarensis. One argument suggests that dimorphism in these early Australopiths was human-like (e.g. Reno, et al. 2003), another suggests it was probably more substantial than that, perhaps approaching or even surpassing what we see in species of gorillas today (e.g. Plavcan, et al. 2005). While I think the bulk of the evidence, including the most recent footprints, support the latter conclusion, at the heart of the issue is one of sample size. Inferring the degree of sexual dimorphism involves inferring the distribution of male and female body size. This is hard because while we have lots of fossils, we cannot always know whether or not they come from male or female individuals. Additionally, the number of fossils that come from the same, time-constrained geological layers, is even smaller, adding an additional degree of uncertainty associated with time-averaging. There is also a lot of potential error that gets introduced when we are using limited samples to simultaneously infer multiple distributions of variance. So while I think the evidence is pretty strong that early Australopiths had moderate to considerably more dimorphism than living humans, that idea still falls pretty squarely in the “hypothesis” zone of scientific knowledge and not the “biological truth” category, to use Coyne’s phrasing.

The second is that inferring human behavioral correlates with estimates of body size dimorphism in our evolutionary past is difficult because humans are outliers to many larger primate patterns in this regard. Coyne anecdotally references some of the common aspects of size dimorphism in primates. Anthropoid primate species do, on average, show considerable size dimorphism, and this does seem positively correlated and causal in some ways with male and female reproductive behavior. However…comprehensive reviews of dimorphism in extant primates suggests that canine dimorphism is actually a more telling morphological indicator of mating behavior than body size dimorphism (see numerous works from Michael Plavcan reviewing primate sexual dimorphism, though Plavcan-2001 and Plavcan-2013 are good places to start). Intriguingly, a key morphological trait typically invoked in the divergence of hominins from other apes is a reduction in canine size and dimorphism. Human canine teeth today are essentially non-dimoprhic.

Furthermore, anthropoid primates tend to be more dimorphic the larger they are, as a species, in terms of body size. Humans are relatively large as far as extant and fossil anthropoid primates go, but actually have only moderate size dimorphism. If we accept the inference that early hominins had more size dimorphism than we do today, then hominin evolution has been characterized by reduced levels of size dimorphism as we have gotten larger, contrary to the larger primate pattern.

Finally, human groups are quite a bit more variable than most well-studied primate groups in both the morphological end of things and the behavioral end of things. Human sexual size dimorphism is moderate, on average, but is also characterized by large intrasex distributions of variation. This creates a huge overlap in size between individual males and females. Human body size is also quite plastic with respect to ecological resources (i.e. we can carry a whole lot of fat mass or not much at all). Normative human sexual and mating practices are also quite varied between traditional cultural groups. Across (and in some cases within) traditional human cultural groups it is possible to sample a broader array of normative tendencies in terms of both male and female promiscuity than we tend to see in primates.

There are a lot of potential reasons why human dimorphism is hard to understand, and most of them come down, at some level, to the importance of the greatly extended period of development that humans experience. We are adolescents for a long time, and even given that long time, we undergo a lot of change relative to our primate relatives. And a lot of that development has to do with complex interactions between social systems (or culture, at some basic level) and our developmental biology.

Kids are wonderfully pluripotent

Because of these factors, making the leap from body size or skeletal size dimorphism to biologically determined sexual behaviors is really challenging. Actually, not just challenging, but speculative.

Dunsworth’s argument, as I read it, was not so much that female body size and mating practices are the primary focus in the evolution of dimorphism in humans, which is how I read Coyne’s reading of it. Instead, it is that there is no a priori reason to give a male-centered view prime billing. And indeed, there is a VAST set of reasons (i.e. history) to be wary of the inaccuracies and damage introduced by male-bias in the perspective of science. As Dunsworth writes:

Knowledgeable people aren’t objecting to facts, as Coyne suggests. They’re objecting to biased story-telling and its annoying and harmful consequences, which Coyne doesn’t acknowledge or grapple with in his piece.

Such an assumed perspective also potentially misleads our basic understanding of evolution itself. In the very Adam Gordon piece that Coyne initially cites in his argument for the primacy of sexual selection on human males, Gordon writes:

Model results suggest that microevolutionary changes in SSD [sexual size dimorphism] can result from greater selection acting on males or females, and that natural selection or natural and sexual selection combined, rather than sexual selection alone, may sometimes explain sex-specific selection differentials. (for more from Gordon on this topic, see Gordon, 2013)

It is almost as if an implicit bias led Coyne to gloss over this conclusion.

Good science is more than just the passive accumulation of observations and their methodological interpretation. Good science is also aware and constantly attentive to our own role and biases as observers, and our obligations to convey the knowledge we produce hand in hand with its limitations. These practices work to ensure that the knowledge science produces really is giving us a better understanding of the world. I cannot recommend enough this recent post from anthropologist Patrick Clarkin, “Pursuing the God of Truth in a Post-Truth Era.”

First, a long look in the mirror is an essential place to start. The shortcomings we see in others reside within us as well. Having a healthy understanding of our own common shortcomings leads to possible solutions and workarounds. It’s why democracies try to build in checks and balances into the system (“If men were angels, no government would be necessary”). This is also why science has a system of peer review, to cross-check another’s work and to try to minimize our shortcomings.

Dunsworth is a good scientist. Coyne would do well to pay attention to her expertise, which is, after all, in the field of human evolutionary biology, rather than simply assume others will defer to his own expert status. Coyne is a good scientist, too. Indeed, I have my own dog-eared copy of Coyne and Orr’s Speciation courtesy of a summer field season on which it accompanied me. But that’s the point. Good scientists still have blind spots, and biological truths, to the extent that they exist, come through adherence to a process, not assertion and wikipedia.

Works Cited:

Gordon, A. D. 2006. Scaling of size and dimorphism in primates II: Macroevolution. Int. J. Primatol. 27:63-105.

Masao, F. T., et al. 2016. New footprints from Laetoli (Tanzania) provide evidence for marked body size variation in early hominins. eLife, 5:e19568.

Reno, Philip L., et al. 2003. Sexual dimorphism in Australopithecus afarensis was similar to that of modern humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100.16: 9404-9409.

Plavcan, J. Michael, et al. 2005. Sexual dimorphism in Australopithecus afarensis revisited: How strong is the case for a human-like pattern of dimorphism?. Journal of Human Evolution 48.3: 313-320.

Plavcan, J. Michael. 2001. Sexual dimorphism in primate evolution.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 116.S33: 25-53.

Plavcan, J. Michael. 2012. “Sexual size dimorphism, canine dimorphism, and male-male competition in primates.” Human Nature 23.1: 45-67.

Gordon, Adam D. 2013. Sexual size dimorphism in Australopithecus: current understanding and new directions. The paleobiology of Australopithecus. Springer Netherlands. 195-212.